By Anne M. Filiaci, Ph.D.

Late nineteenth century Americans called young girls who did the housework and watched over their siblings “Little Mothers.” These unpaid child workers lived lives of unremitting drudgery. Florence Kelley would later speak of the pernicious and pervasive nature of this type of child labor, even as other forms became illegal. She noted that while “manufacture and commerce are [often] closed to children under the age of fourteen years,” (Kelley, p. 33) the existence of the tenement sweatshop

" order_by="sortorder" order_direction="ASC" returns="included" maximum_entity_count="500"]means boys and girls of ten years [are] kept at home from school, in violation of the compulsory education law, to do the housework and take care of the younger children while the mother sews for the market. (Kelley, p. 238)

Kelley argued that as long as tenement labor persisted, it meant that “the drudgery of ‘little mothers’” would be allowed to “occupy the earlier years.” (Kelley, p. 33)

Lillian Wald wrote vividly about the lives of this invisible workforce, with anecdotes depicting real people she met as she worked among the sick poor. One such story was of a small girl, a child whose “picture” she could not “efface from” her “memory.” She had “found” the “little eight-year-old girl”

standing on a chair to reach a washtub, trying with her tiny hands to cleanse some bed-linen which would have been a task for an older person. Every few minutes the child got down from her chair to peer into the next room where her mother and the new-born baby lay, all her little mind intent upon giving relief and comfort. She had been alone with her mother when the baby was born and terror was on her face.” (Wald, pp. 73-4)

Wald told another story about a “Little Mother” named Annie. Annie was one of “three little girls, daughters of a skilled cobbler” who were members of “the first party of children that we [in the Nurses’ Settlement] sent to the country” for a “Fresh Air” vacation. The girls’ mother was, according to Wald, “a complaining, exacting invalid,” who “spent a large proportion of her husband’s earnings for patent medicines.” Annie, who was “not quite twelve, was the household drudge.” Wald arranged to send the mother to a hospital while the children were away. Their two-week vacation in the country turned out to be a resounding success. While disembarking from the train, they displayed such “joyousness and bubbling spirits” that they “attracted the attention of the onlookers.” However, as they approached their home, Wald observed that Annie’s

responsibilities fell like a heavy cloud upon her, and before we reached the tenement she was silent. Her quick eye discerned the absence of the brick which had kept the front hall door open, and in a second she had darted into the yard and replaced it. Before we left, with sleeves rolled up she was beginning to wash the pile of dishes that had accumulated in her absence. Gone was the gayety. The little drudge had resumed her place.

Wald kept track of Annie, and noted that the young girl, desperate to escape her lot, sought outside employment even before she was old enough to legally join the workforce. Annie swore “falsely to her age” to a “notary public” in order to obtain “employment papers.” With these papers, she “secured” a “position…as cash girl in the basement of a department store.” To Annie, Wald said, this tedious, underpaid and exploitative work seemed no less than an “emancipation” from hateful household labor—with the added benefit of “an opportunity for fellowship” with girls of her own age. (Wald, pp. 75-77)

Muckraking journalist Jacob Riis—friend and mentor to Wald—also used anecdotes to publicize the plight of “little mothers” among the working poor on the Lower East Side. He depicted a world of a “hundred little companions in the alley,” where “the ‘smaller girls “minded the baby,” leaving the mother free to work, while siblings “made artificial flowers” and “paper-boxes,” “earned money at ‘shinin’’ and sold newspapers.” (Riis, p. 111)

Riis revealed how sometimes, in the absence of parents, one of the girls in an orphaned family would be assigned the role of “mother” for her working siblings. “Little Katie,” a “nine-year-old housekeeper of the sober look,” was one of these. Riis met Katie “in the Fifty-second Street Industrial [school], where she picked up…crumbs of learning…in the intervals of housework.” Riis noted that for Katie, “the serious responsibilities of life had come early.” She lived on “the top floor of a tenement in West Forty-ninth Street” where she, along with “her older sister and two brothers,” had moved “when their mother died and the father brought home another wife.” Katie’s older siblings “worked in the hammock factory, earning from $4.50 to $1.50 a week.” They bought their furniture “on instalments” while

Katie did the cleaning and cooking…. scrubbed and swept and went to school, all as a matter of course, and ran the house generally, with an occasional lift from the neighbors in the tenement. (Riis, pp. 60-61.) (Katie’s picture appears on pp. 114-117 of Riis’ Children of the Poor. See below.)

Katie was not the only Little Mother whom Riis encountered in his forays into night school. He noted that

“In an evening school class of nineteen boys and nine girls which I polled once I found twelve boys who ‘shined,’ five who sold papers, one of thirteen years who by day was the devil in a printing-office, and one of twelve who worked in a wood-yard. Of the girls, one was thirteen and worked in a paper-box factory, two of twelve made paper lanterns, one twelve-year-old girl sewed coats in a sweat-shop, and one of the same age minded a push-cart every day. The four smallest girls were ten years old, and one of them worked for a sweater and ‘finished twenty-five coats yesterday’ she said with pride…. The three others minded the baby at home; one of them found time to help her mother sew coats when baby slept.” (Riis, p. 111) (my emphasis)

Throughout the 1890s there were a number of attempts to lighten the work and enhance the lives of these young girls. One was the opening of private pre-schools and kindergartens, often run by women reformers. Riis proclaimed that for little mothers, the “kindergarten is the city’s best truant officer,” because “it ferrets out a lot who are truants from necessity, not from choice, and delivers them over to the public school.” He explained that

There are lots of children who are kept at home because someone has to mind the baby while father and mother earn the bread for the little mouths. The kindergarten steps in and releases these little prisoners. If the baby is old enough to hop around with the rest, the kindergarten takes it. If it can only crawl and coo, there is the nursery annex.” (Riis, p. 181)

Wald actively supported the “release” of Little Mother “prisoners” through the vehicle of the private kindergarten. Helen McDowell, one of the Settlement’s lay (i.e., non-nurse) residents, owned a residence on East Broadway that backed up to the Henry Street Settlement. McDowell, fondly known as Tante Helene, opened “her house to every demand made upon it.” She hosted a kindergarten there, as well as many other entertainments for girls who watched their siblings. Focusing on the needs of children, she was

constantly busy in organizing some fun or frolic for the young people—a Kinder symphony, theatricals, recitations, or a musical party. A kindergarten occupies one floor in the mornings, the teachers of which are supplied by the New York Kindergarten Association, and their functions are among the prettiest that take place in the house. (Duffus, pp. 66-67, James, Dock Reader, p. 33-34)

When the Settlement opened its renowned backyard playground, Wald tried to give priority to girls who cared for younger siblings, literally allowing Little Mothers to go to the front of the line. However, to her amusement and consternation, children constantly came up with ingenious ways to circumvent this show of preference. Once they “learned that ‘little mothers’ and their charges had precedence,” children fought about “who should hold the family baby.” When a family had no baby, one “was borrowed.” Sometimes “[s]ix-year-olds, clasping babies of stature almost equal to their own,” stood “outside [the playground], hoping to attract attention to their special claims.” (Wald, pp. 83-84)

Perhaps the most organized attempt to specifically address the unremitting labor of Little Mothers came before the Henry Street Settlement even existed, with the formation of Little Mothers’ Aid Societies in the early 1890s. Prosperous New York women organized and joined the societies in order to bring young girls who minded their siblings some small amount of relief. The Little Mothers’ Aid Societies did not seek to pass laws or to radically alter the lives of “Little Mothers.” Instead, they focused on providing brief periods of respite and in other ways easing the burden thrust upon these young children.

Jacob Riis spoke approvingly of these women in his 1892 work, Children of the Poor. “The ‘Little Mothers’ Aid Society,” he wrote, reaches

out for the little home worker whose work never ends, the girl upon whom falls the burden and responsibility of caring for the perennial baby when scarcely more than a baby herself, often even the cooking and all the rest of the housework so that the mother may have her own hands free to help earn the family living. (Riis, pp. 172)

The year before Children of the Poor was published, the work of the Little Mothers’ Aid Society was the subject of a laudatory fundraising appeal that appeared in the New York Times. The article, published in July of 1891, described the organization’s goals and its work in detail, noting that its “plan” was to provide day-long holiday “outings” and other types of relief to

the little girls in the families of the poor whose melancholy lot it is to be burdened with the care of younger brothers and sisters, and often with the entire charge of the household.” (New York Times, July 5, 1891)

The Times article also gave a general report of the organization’s activities over the previous year, noting that the Society had provided “A days’ outing, with food, necessary clothing in cases where the children were but half clad, medical attendance and comforts for the sick” to “944 little mothers and their sisters.”

In addition to the self-congratulatory observation that there were “‘over 1,000 on our list to whom we have given their only happy days,’” the Society’s president, Mrs. Alma Colder Johnston (aka Alma Calvin Johnson) also reported that the Society had provided medical aid and support to the little girls. The organization, she said, had “‘cared for 20 through long illnesses, clothed 380, and entertained 2,000 “little mothers” and their sisters; have employed physicians” to watch “over the children during the outings,” and had continued medical assistance throughout the year to those “most requiring it.”

The Society also sent “‘[s]even women’” to visit the tenements, where they arranged “‘for the care of the “perpetual baby”’ while the “little mothers” went on their “holiday.” The group also worked with “‘the various “fresh air” organizations’” to send “‘as many “little mothers” as can be spared away for two weeks.’” The society’s future plans included loaning out baby carriages to little mothers.

Depending on the results of their fundraising drive, the Little Mothers Aid Society also planned to take groups of these girls “to Pelham Bay Park for a day’s outing, a bath under competent medical advice in the still waters of the Sound, with food, flowers, and fruit to their one day’s satisfaction.’” In anticipation of the holiday, the Society had already secured “‘use of a fine old mansion in the park’” from the Park Department. This mansion had been “‘dedicated as a “Little Mothers’ Holiday House.’” The Society had also obtained “‘free transportation’” from the Belden Brothers “by their City Island line of pleasure steamers.’” (New York Times, July 5, 1891)

The fundraising appeal must have been a success, because the next year Riis was able to report that the Society finds “[t]hese little slaves,” pays a “nursery” to

care for their charges

“if need be, and carries the little mother off for a day in the woods up at Pelham Bay Park where the Park Commissioners have set a house on the beach apart for their use in the summer months.” (Riis, p.172)

The Mothers Aid Society did not attempt to end this kind of child labor, instead choosing to ameliorate the situation by easing the burden on these young workers. Their efforts also served to publicize the nearly invisible plight of “Little Mothers.” Florence Kelley—who tirelessly fought to end child labor—hoped this form of it would disappear with the abolition of tenement sweatshops. Yet even Kelley underestimated the persistence of the drudgery of “little mothers”—who even today labor invisibly, doing housework and minding younger siblings—mostly without pay—throughout the world.

Bibliography

Bell, Blake A., “The Little Mothers Aid Association and its Use of Hunter’s Mansion on Hunters Island in the Late 19th and Early 20th Centuries,” Friday, April 15, 2016, http://historicpelham.blogspot.com/2016/04/the-little-mothers-aid-association-and.html Current 5/27/20

Bell, Blake A., “More on the Little Mothers Aid Association and its Use of Hunter’s Mansion on Hunter’s Island,” Thursday, June 28, 2018, http://historicpelham.blogspot.com/2018/06/more-on-little-mothers-aid-association.html Current 5/27/20

Daniels, Doris Groshen, Always a Sister: The Feminism of Lillian D. Wald, New York, Feminist Press, 1989.

Duffus, R.L., Lillian Wald: Neighbor and Crusader, New York: The Macmillan Company, 1939. (Duffus, pp. 66-67)

James, Janet Wilson, ed., A Lavinia Dock Reader, edited with a biographical introduction by Janet Wilson James, New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1985. (James, Dock Reader, p. 33-34)

Kelley, Florence, Some Ethical Gains Through Legislation, by Florence Kelley, New York: The Macmillan Company, 1905. (Kelley, pp. 33, 238)

New York Times, “Help the ‘Little Mothers.’ What the Aid Society Has Done and Would Like to Do,” New York Times, July 5, 1891. (New York Times, July 5, 1891)

Riis, Jacob, The Children of the Poor, New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1908 (c1892). (Riis, pp. 60-61, p. 111, p. 172, p. 181) http://archive.org/stream/childrenofpoor00riisuoft#page/20/mode/2up (openlibrary.org) Current 5/1/2020.

Trattner, Walter I., Crusade for the Children: A History of the National Child Labor Committee and Child Labor Reform in America, Chicago: Quadrangle Books, 1970.

Wald, Lillian D., The House on Henry Street, NY: Henry Holt & Co., 1915. (Wald, pp. 73-77, pp. 83-84)

Illustrations

“i scrubs.”—katie,

who keeps house in

west forty-ninth street.

From Riis, Jacob, The Children of the Poor, New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1908 (c1892), Chapter VI, p. 61. Image from https://www.gutenberg.org/files/32609/32609-h/32609-h.htm#CHAPTER_IV Current 5/1/2020.

minding the baby.

From Riis, Jacob, The Children of the Poor, New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1908 (c1892), Chapter VI, pp. 114-117. Image from Link to Illustration Current 5/1/2020.

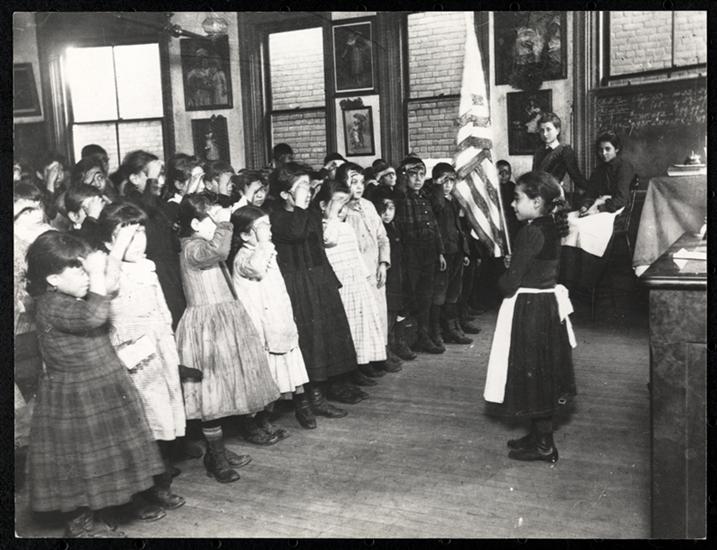

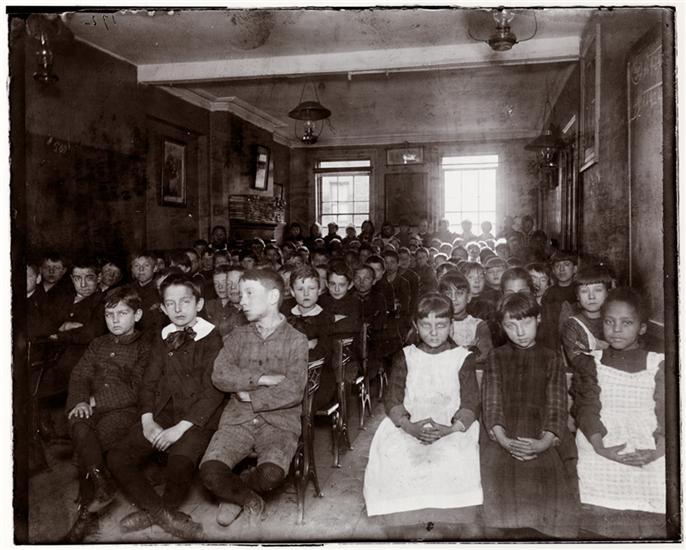

Fifty-Second Street Industrial School Link to Illustration

Jacob A. (Jacob August) Riis (1849-1914), Saluting the Flag in the Mott Street Industrial School. DATE:ca. 1890 Young students salute the American flag at Mott Street Industrial School. Museum of the City of New York Images. Link to Illustration Current 6/30/20

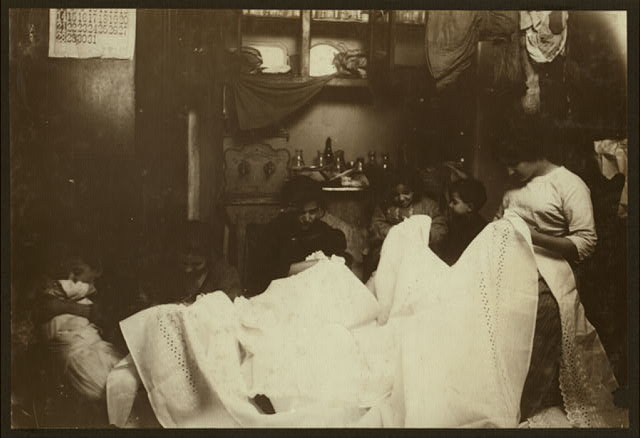

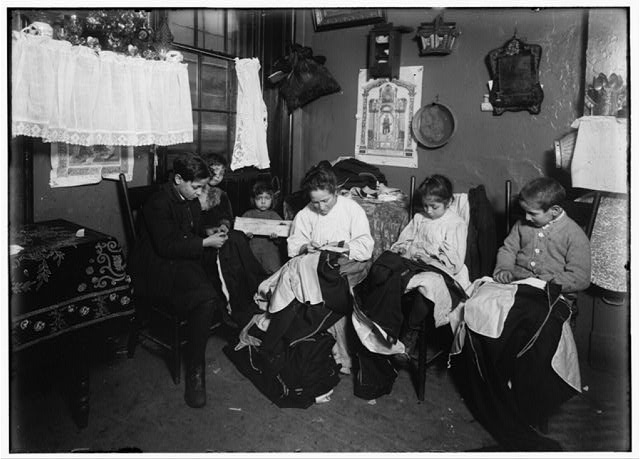

Hine, Lewis Wickes, photographer. [1 P.M. Family of Onofrio Cottone, 7 Extra Pl., N.Y., finishing garments in a terribly run down tenement. The father works on the street. The three oldest children help the mother on garments. Joseph, 14, Andrew, 10, Rosie, 7, and all together they make about $2 a week when work is plenty. There are two babies.Location: New York, New York State]. January, 1913. Image. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, Link to Illustration Current 6/24/20

Hine, Lewis Wickes, photographer. Cutting out embroidery on the dirty kitchen floor. Battista family, 259 E. 151 St. N.Y. On the right is the married daughter, who lives down stairs and usually works there. On her right next to the boy is Flora, said to be 9 years old and very much stunted in size. “Been sick.” Next to her is the mother and next is Linda, 11 years old. The baby, dirty and covered with sores, was being handed about. Probably has impetego. Location: New York, New York State. January, 1912. Image. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, Image. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, Link to Illustration Current 6/24/20

Hine, Lewis Wickes, 1874-1940, photographer, Title: Jessie D—- (the tallest girl) and some of her charges. Girl in doorway is her boon Companion. Location: Cincinnati, Ohio. Creator(s): Hine, Lewis Wickes, 1874-1940, photographer Date Created/Published: 1908 August. Medium: 1 photographic print.

Reproduction Number: LC-DIG-nclc-04453 (color digital file from b&w original print)

Rights Advisory: No known restrictions on publication. For information see: “National Child Labor Committee (Lewis Hine photographs),” https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/res.097.hin

Access Advisory: For reference access, please use the digital item to preserve the fragile original item. Call Number: LOT 7483, v. 1, no. 0021 [P&P]

Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print Notes: Title from NCLC caption card.

Attribution to Hine based on provenance. In album: Miscellaneous. Hine no. 21.

Credit line: National Child Labor Committee collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. General information about the National Child Labor Committee collection is available at: https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.nclc

Forms part of: National Child Labor Committee collection. Format: Photographic prints.

Collections: National Child Labor Committee Collection Bookmark This Record: Link to Illustration Current 6/30/20

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. “Shelling nuts at home” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1900 – 1937. Link to Illustration Current 6/24/20

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. “Shelling pecans at home” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1900 – 1937. Link to Illustration Current 6/24/20