By Anne M. Filiaci, Ph.D.

Background 1874-1898

Wald believed that every child who was capable of learning deserved to go to school—poor as well as rich, sick as well as healthy, learning disabled as well as gifted. “The public school has the power,” she wrote, “to bring within its walls all the children physically and mentally competent to attend it.”

" order_by="sortorder" order_direction="ASC" returns="included" maximum_entity_count="500"]To Lillian Wald, both the government and the family not only had an obligation to send children to school—they also had much to gain by doing so. Those who got an education had an infinitely greater chance to overcome poverty and achieve success as adults. At the very least, they were more likely to become useful citizens and less likely to become criminals.

By the time Wald moved to the Lower East Side in 1893, laws mandating school attendance had been on the books for almost twenty years. New York State had passed a Compulsory Education Law as early as 1874. However, since the law did not include funding for fighting truancy, it was difficult to enforce.

In 1894, New York State passed another compulsory education law. The new law mandated school attendance for children between the ages of eight and twelve. Children between the ages of twelve and fourteen could go to work only if they had a “permit” and could prove that they had attended classes for eighty consecutive days during the school year. Children who were over fourteen years of age did not have to attend school at all.

Unfortunately, enforcement of the 1894 law also proved to be a problem. As long as parents or guardians informed the school that they were unable to compel their children to attend, they were not held responsible. Many parents who needed or wanted their children to go to work instead of school took advantage of this loophole.

Much of American society tacitly supported these parents, believing that the family was the basic unit of society, and that the state had no authority to supersede the right of a family to earn income from its children. Most truant officers and many school officials and judges were also sympathetic. They hesitated to override parental decisions, and looked the other way as long as children were not hanging around in the streets causing a public nuisance. The law was thus mainly enforced to control unemployed children who were rowdy and roamed in gangs.

American society’s overwhelming reluctance to overrule parents’ authority over their children was one of the major stumbling blocks to achieving the progressive goal of universal public education. Rather than fighting this deeply-entrenched attitude directly, reformers instead chose to focus on outlawing most forms of paid work for children, especially if the work took place during school hours or affected a child’s ability to learn. Reformers used the laws against child labor, passed during the same period, in conjunction with more strictly enforced compulsory education laws, in order to keep as many children in school as possible.

Over the course of many years, Wald and her colleagues gradually achieved some success. Going against child labor in factories proved one of their most fruitful methods of attack, since many Americans saw industrialization as hostile to the Republic’s agrarian ideal. An 1886 law made it illegal for children under the age of thirteen to work in factories—although they could still work in sweatshops and many other trades. Three years later, the Child Labor Law of 1889 raised the age of legal factory workers to fourteen, and provided that those under sixteen could not work in factories unless they were able to read and write.

The laws against certain kinds of child labor, combined with ever more effective compulsory education laws, did make a difference. Within a year after the 1894 law passed, over 19,000 truant or neglected students throughout the state had been returned to school.

The increasing success of reformers, however, caused another problem. New York City’s public schools could not cope with the influx of students. Schools lacked the facilities to house and educate all who showed up. Thousands were turned away; some were forced to attend half-day sessions.

In addition to the sheer numbers of students, many hailed from diverse cultural and economic backgrounds and possessed varying abilities and/or skill levels. They often came from families that did not speak English at home and knew little of American customs and traditions. While Wald and many of her associates celebrated this diversity, they also knew that it made teaching more challenging.

At the same time that schools were experiencing a mass influx of new students, the structure of public education in New York City was also changing. The City’s new charter went into effect on January 1, 1898, expanding its boundaries to include Manhattan, Long Island, the Bronx, Brooklyn, Richmond County, and parts of Queens. This move boosted school enrollment by five percent, for a total of 500,000.

Residents of the expanded school district elected William H. Maxwell as their first Superintendent of Public Instruction in 1898. From 1887 until 1898, Maxwell had served as the Brooklyn Superintendent of Schools. In both positions, the Superintendent made clear that he was determined to improve education for the poor and for those who were unable to learn using traditional methods. He saw progressive reformers as his allies in this endeavor.

Now that more students were crowding the schools, the question facing reformers and educators became how to effectively teach the most recalcitrant learners. The new Superintendent moved quickly to consolidate what had been a loose confederation of school districts into a strong centralized organization. This way he could more easily enact programs that would achieve his goals.

Bibliography

The Encyclopedia of New York City, Second Edition, edited by Kenneth T. Jackson, New Haven & London, Yale University Press, 2010. (See “Public schools” entry, p. 1056.)

Hendrick, Irving G. and Donald L. MacMillan, “Selecting Children for Special Education in New York City: William Maxwell, Elizabeth Farrell, and the Development of Ungraded Classes, 1900-1920,” Journal of Special Education, v. 22, no. 4, (Winter 1989) [c2001], pp. 395-417. (See pp. 396-400)

Kode, Kimberly, Elizabeth Farrell and the History of Special Education, Arlington, VA: Council for Exceptional Children, 2002 (ERIC Document ED474364). (See pp. 20-24.)

Mooney, John Vincent, William H. Maxwell and the Public Schools of New York City, (January 1, 1981). Dissertation. Bronx, NY: Fordham University, 1981. Find Abstract to Dissertation at http://fordham.bepress.com/dissertations/AAI8119781/

New York State Archives, Researching the History of Your School: Suggestions for Students and Teachers, New York: The University of the State of New York, The State Education Department, State Archives, 1985. “Milestones” timeline appears at pp. 14-15. Link: http://www.archives.nysed.gov/common/archives/files/ed_researching_school.pdf

Stambler, Moses, “The Effect of Compulsory Education and Child Labor Laws on High School Attendance in New York City, 1898-1917,” History of Education Quarterly, Vol. 8, No. 2 (Summer, 1968), pp. 189-214. (See pp. 190-195.)

Wald, Lillian D., The House on Henry Street, N:Y: Henry Holt & Co., 1915. (See pp. 122-123.)

Wald, Lillian D., Windows on Henry Street, Boston: Little Brown, and Company, 1934.

Illustrations

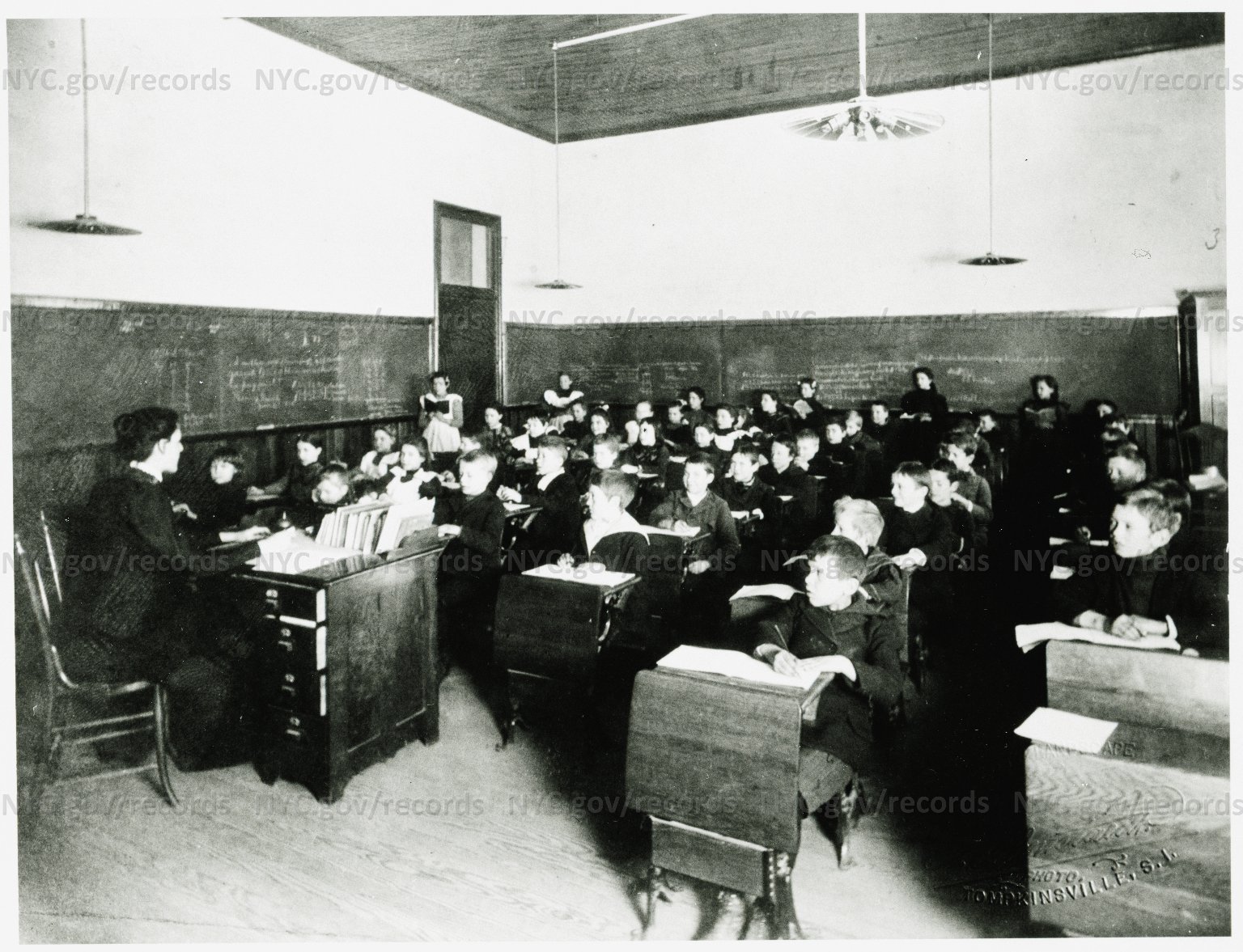

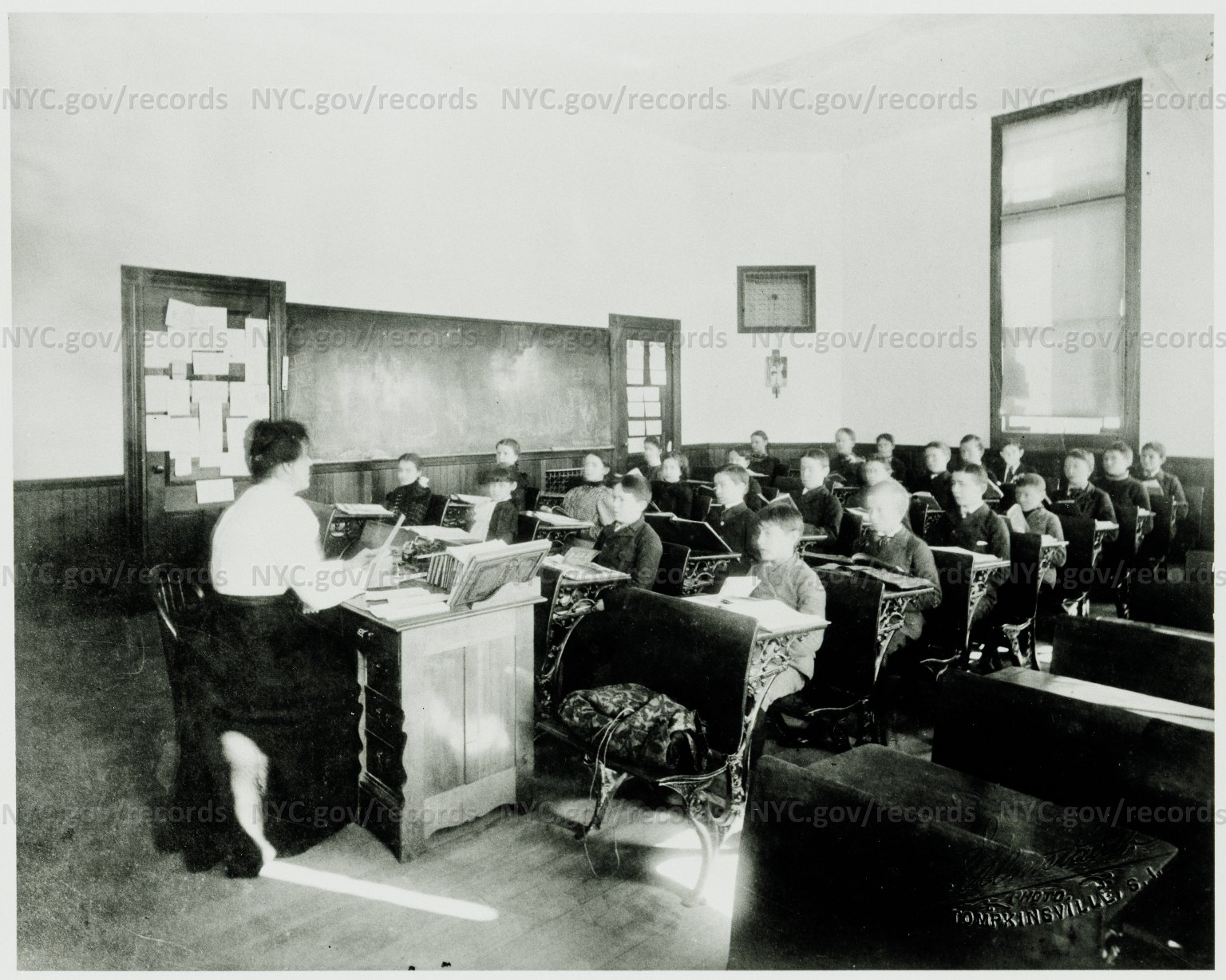

NYC DORIS, Board of Education, P.S. 10, Staten Island: classroom, 1900 (school id is tentative) Link to Illustration Current 2/23/17

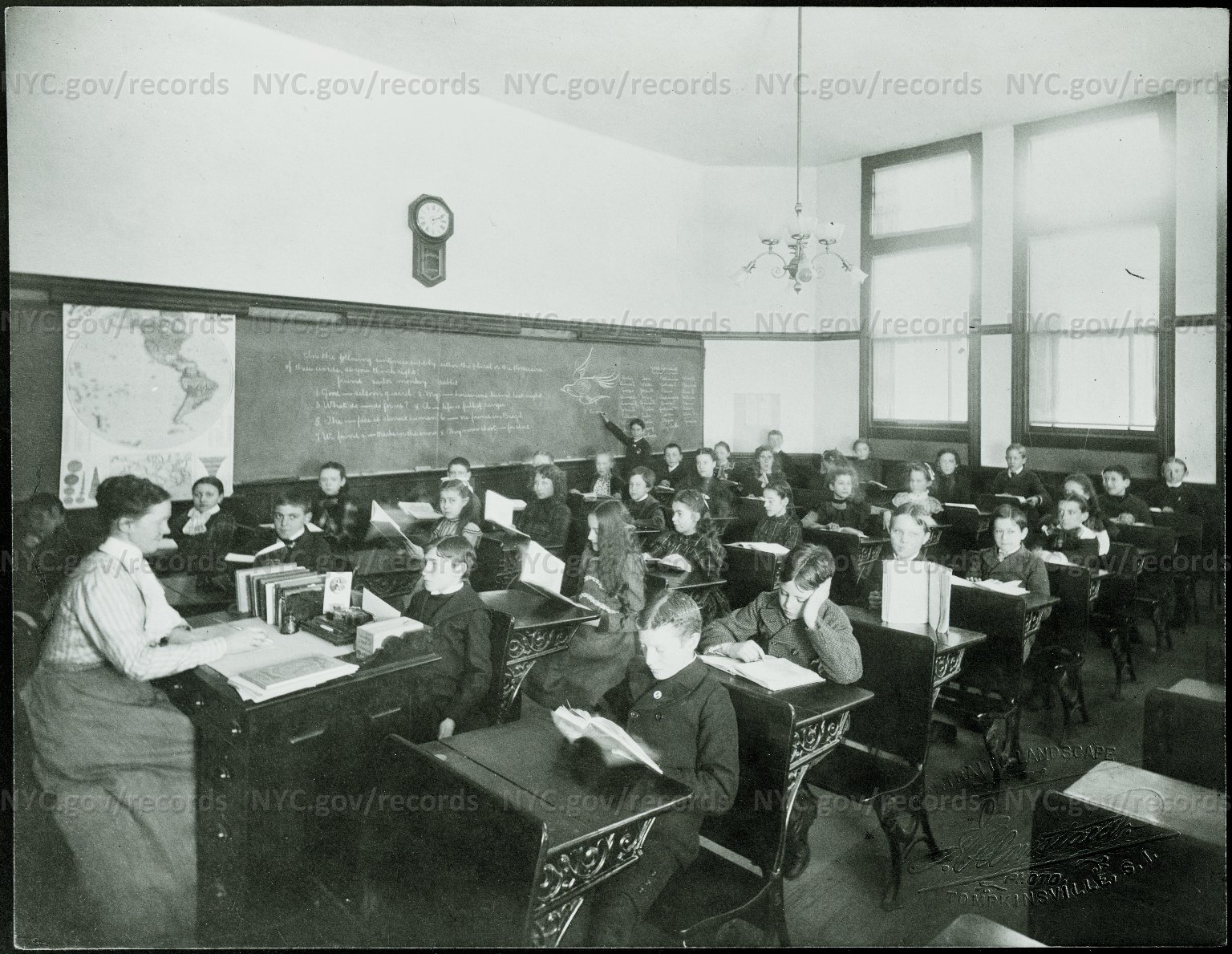

NYC DORIS, Board of Education, P.S. 17, Staten Island: classroom, 1900 (school id is tentative) Link to Illustration Current 2/23/17

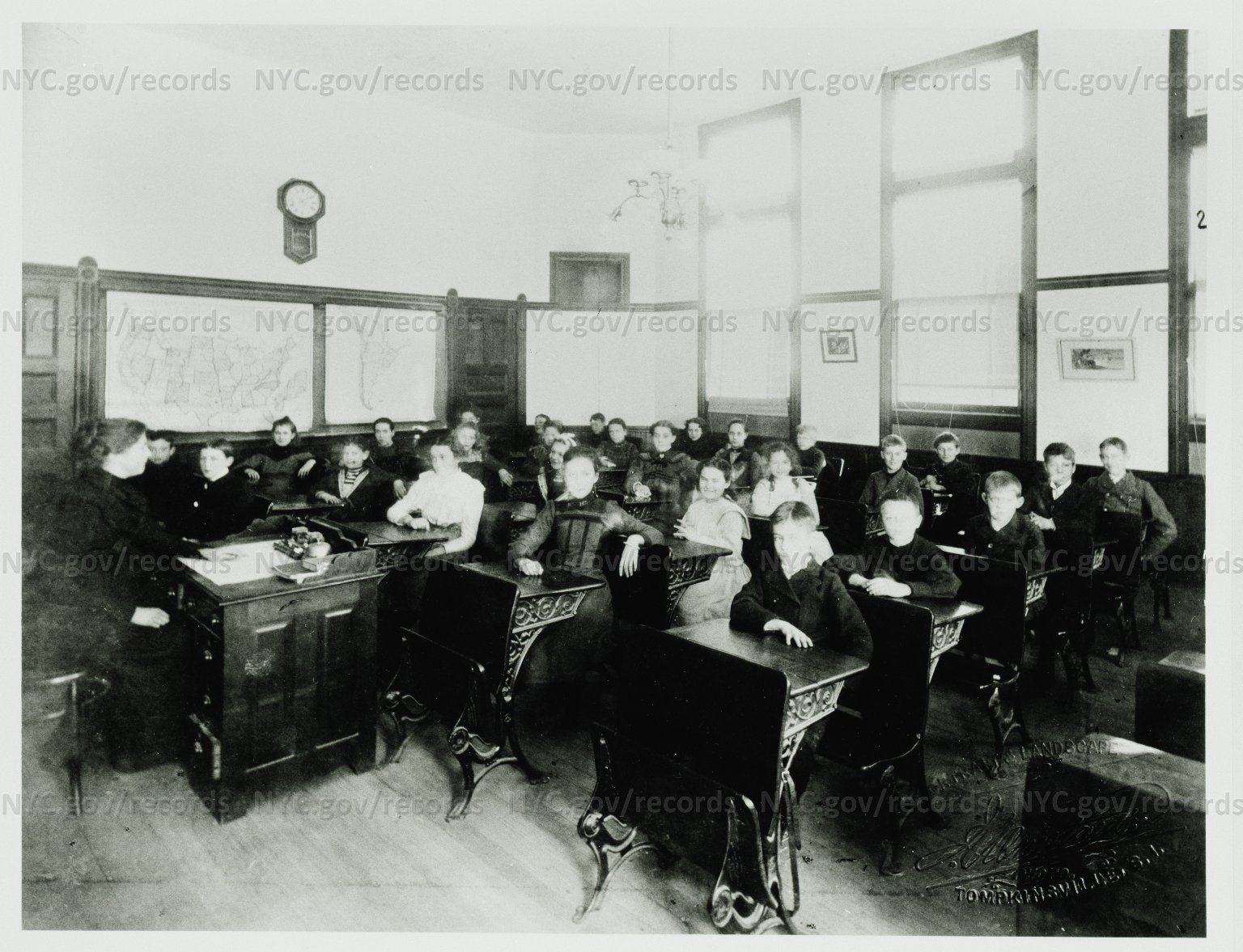

NYC DORIS, Board of Education, P.S. 16, Staten Island: classroom, 1900 (school id is tentative) Link to Illustration Current 2/23/17

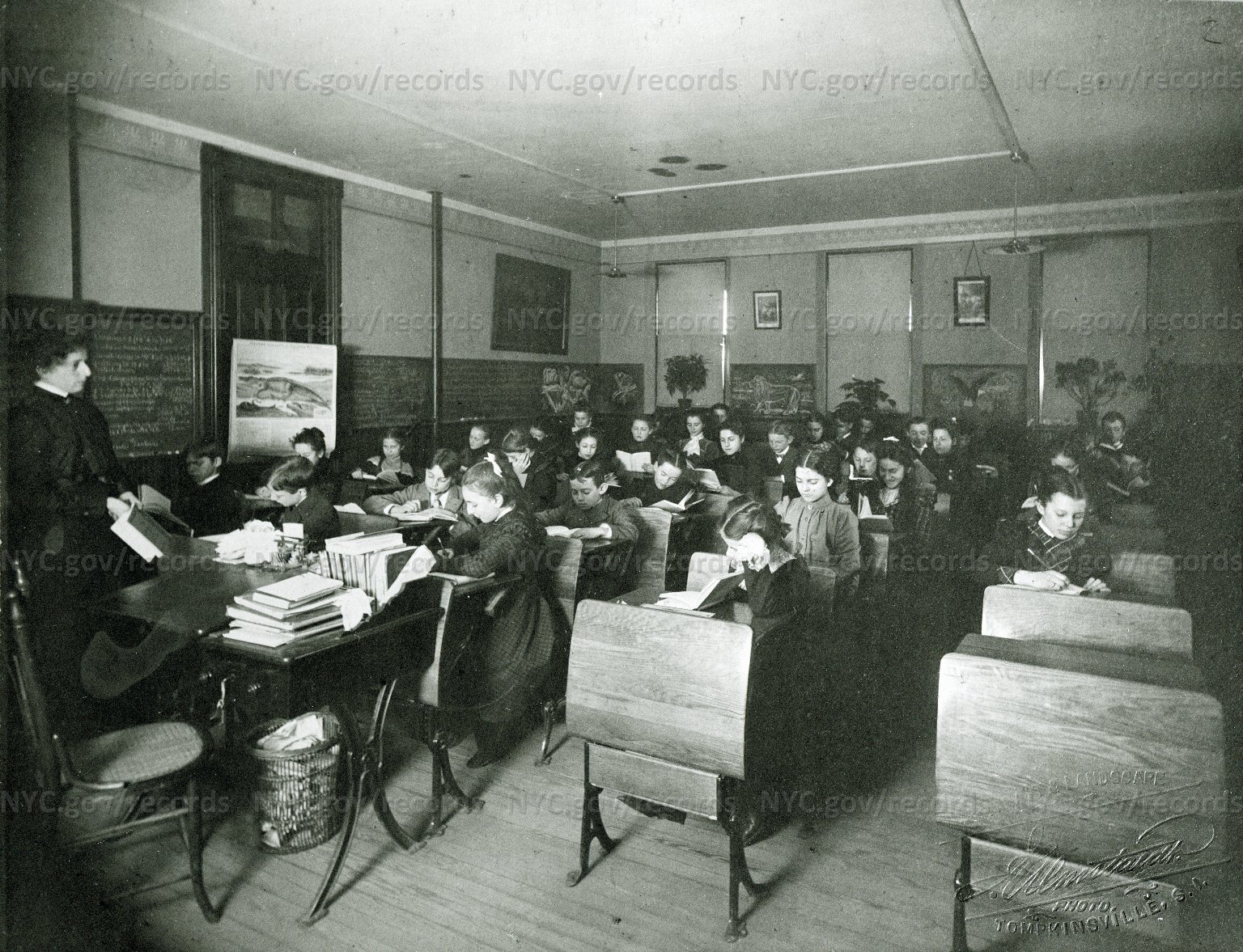

NYC DORIS, Board of Education, P.S. 16, Staten Island: classroom, 1900 (school id is tentative) NYC DORIS, Board of Education, P.S. 16, Staten Island: classroom, 1900 (school id is tentative) Link to Illustration Current 2/23/17

NYC DORIS, Board of Education, P.S. 20, Staten Island: classroom, 1900 (school id is tentative) Link to Illustration Current 2/23/17

NYC DORIS, Board of Education, P.S. 15, Staten Island: classroom, 1900 (school id is tentative) Link to Illustration Current 2/23/17

Copyright Anne M. Filiaci 2017