By Anne M. Filiaci, Ph.D.

In 1895, living conditions continued to be grim for most of New York City’s poor inhabitants, but the reform efforts of Richard Watson Gilder’s Tenement House Committee (1894) did result in some major improvements. In late November of 1896, the New York Times reported that because of “the new laws secured by the [Gilder] committee,…[t]he death rate” had “materially decreased” especially among “children under five years of age.” It was this latter group “who had before experienced the greatest fatality [rate] in the old tenement houses ….” The paper went on to state that the improvement in the health of the youngest residents

was clearly manifested by the way in which the children of the tenements stood the terrible ordeal of the hot spell in last August, when [even] men and horses succumbed to the heat.*

" order_by="sortorder" order_direction="ASC" returns="included" maximum_entity_count="500"]The Gilder Committee recommended general improvements to neighborhoods and public health initiatives as well as specific tenement housing reforms. New York City subsequently adopted new statutes to reflect many of the recommendations.

The enacted reforms were strengthened when New Yorkers elected anti-Tammany candidate Mayor William Lafayette Strong in 1894. Strong, who was in office 1895-1897, hired people who were intent upon zealously and effectively enforcing the new laws. Colonel George E. Waring Jr. (1833-1898) was arguably one of the administration’s most effective advocates of progressive reform. Known for designing and installing sewer systems that separated runoff from domestic waste, Waring became Street Commissioner of the City of New York in 1895.

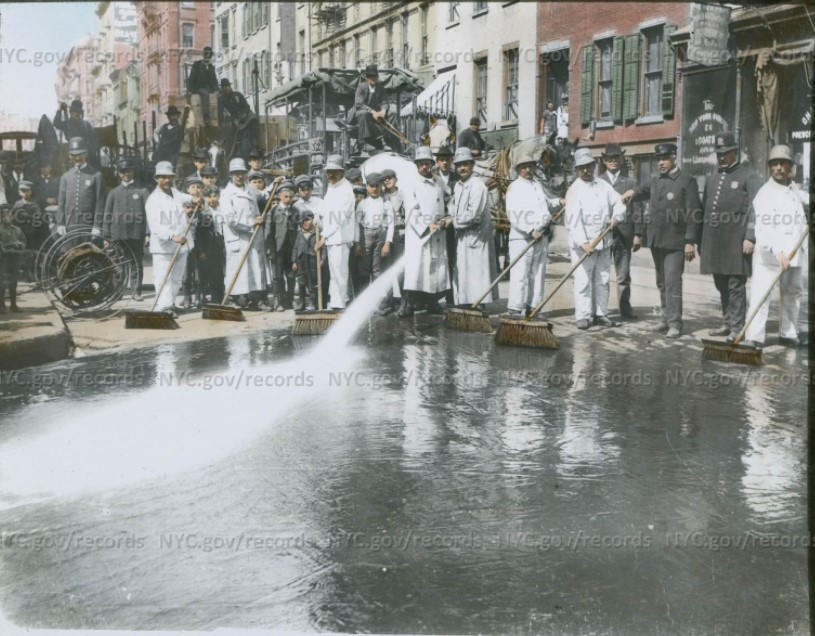

When Colonel Waring started his job, New York City’s streets were filled with mounds of disease-breading filth that included—in addition to everyday garbage—rotting animal carcasses and pig, horse, dog and human manure. Under Waring’s command, the city’s sanitation workers—called “White Wings” because their uniforms were white from head to toe, including white capes resembling wings—swooped in, cleaning the city’s streets of garbage for the first time. In the few years that he served, the colonel

drew on his wartime experience and his experience as a sanitation engineer to introduce innovations—including comprehensive and systematic street sweeping, a uniformed cleaning and collection force, and mandated recycling—that were copied by cities around the country….**

Waring died in 1898, ironically as a result of yellow fever he contracted while cleaning up Cuba during the Spanish American War. The New York Times eulogized him in an extensive article, declaring

[t]he cleaning of the streets of New York, for the first time during the memory of its oldest inhabitant,… [was] the most conspicuous and doubtless the most widely beneficial of his works.

The Times continued, noting that as Street Commissioner, Waring was able to apply the “theoretical and practical knowledge which he had acquired in his profession of sanitary engineering.” Yet his “administrative ability” and his “military experience” were arguably even more important, according to the Times. “He found the street-cleaning force a rabble, and he left it an army,” the article proclaimed. Indeed, Waring’s “street-cleaning force” was so effective and so popular that when they men took part in parades they were met with public “cheering.”

The Times attributed Waring’s introduction of a meritocracy to the transformation of both the force and the public’s perception of it.

The force that paraded amid the plaudits of its fellow-citizens was composed in great part of the same men who had composed it before. But whereas it had been composed of men who owed their places to ‘politics,’ and whom nobody had ever thought of applauding any more than they had thought of applauding themselves, it had become a force of men who owed their places to the faithful performance of their work, and who had had self-respect infused into them by the consciousness of that fact….

Because of Waring’s work, according to the Times, there was “not a man or a woman or a child in New York” who did “not owe him gratitude for making New York, in every part, so much more fit to live in than it was when he undertook the cleaning of the streets.”

Many progressive reformers also heaped accolades on Waring and his work. Jacob Riis penned a famous quote—“It was Colonel Waring’s broom that first let light into the slum.” Georgia Beaver Judson, one of the first members of Lillian Wald’s Henry Street family—“the fourth nurse whom Miss Wald asked to join her”—later in life remembered the Colonel’s work—

Henry Street and its environs, Cherry street and the narrow by-paths of the Lower East Side, were then a seething mass of decay and disorder. Refuse was thrown into the streets to fester and decay and breed disease.

Came Colonel Waring and his White Wings, who did more for health than any other agency in New York. He cleaned the disease-breeding streets, the streets seething with decay and decomposition.

Wald also praised Waring on more than one occasion. In her oft-told story of the experience that brought her to her life’s work—being “led” over broken roadways…over dirty mattresses and heaps of refuse,” she made sure to add that this all happened “before Colonel Waring had shown the possibility of clean streets even in that quarter, — ….”

The first boys’ club at the Henry Street Settlement, called the American Heroes Club, discussed a prominent American at every meeting. At Wald’s prompting they “gave an honored place to Colonel Waring, who cleaned the streets….” But Wald did not have to work hard persuade the neighborhood boys that Waring deserved a place in their pantheon of heroes. Another boy’s group, the Hawthorne Club, met at the Settlement “in the days when Colonel Waring’s big broom was sweeping the neglected East Side…” This club “found itself more interested in clean streets than in literature.” One club member “got up” during a meeting “to propose a change of name” for the club, demanding, “What did Hawthorne ever do for clean streets?’”

The combination of the 1895 Tenement Law, a reform administration willing to enforce it, and the genius of Colonel Waring led to real accomplishments in the city’s efforts to make its environment cleaner, healthier and safer. Just one year later, Richard Gilder looked back in pride at the changes—“‘The new laws,’” he said,

“‘were strictly carried out. Col. Waring’s work in cleaning the streets, the enforcing of better sanitary conditions in the tenements, more stringent and better health laws, the asphalting of the streets, and the improvement [of] the tenement houses themselves have all contributed in the bettering of conditions among the poor, who have to live in those overcrowded quarters.’”

——-

*But more work was needed. The summer, beginning in June, was known as “the… diarrhoeal season,” and even as late as 1908 “1500 babies each week [died] all through the hot weather.” (data from Josephine Baker, Chief of the City’s Division of Child Hygiene)

** The “mandated recycling”—which had already been introduced in Boston—had households separate out ash and food waste from the rest of their garbage.

Bibliography

Baker, S. Josephine, Fighting For Life, NY: The Macmillan Company, 1939.

“Colonel Waring,” New York Times, October 30, 1898.

Duffus, R.L., Lillian Wald: Neighbor and Crusader, New York: The Macmillan Company, 1939.

Lee, Jennifer 8, “He Cleaned the Streets, and Left the Presidency to Others,”

Section: City Room, Blogging from the five boroughs, New York Times, October 1, 2009 12:56 PM http://cityroom.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/10/01/he-cleaned-the-streets-and-left-the-presidency-to-others/?_r=0 Current 8/9/16 (link is only working in Chrome).

New York City, Department of Sanitation About, History http://www1.nyc.gov/assets/dsny/about/inside-dsny/history.shtml (Current 8/3/16).

“Reform in Tenements: Health and Morals of Their Inmates Improved,” New York Times,November 28, 1896.

Wald, Lillian D., The House on Henry Street, N:Y: Henry Holt & Co., 1915.

Wald, Lillian D., Windows on Henry Street, Boston: Little Brown, and Company, 1934.

Whelan, Anne, “Georgia Beaver Judson, a Pioneer With Lillian Wald; Little Realized Inevitable Scope of Settlement Work,” The Bridgeport Sunday Post, June 4, 1939.

Illustrations

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. “Street sweeper with hand cart.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1896. Link to Illustration 10/1/21

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. “Street sweeper.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1896. Link to Illustration Current 10/1/21

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. “Street sweeper.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1896. Link to Illustration Current 10/1/21

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. “Policeman & street sweeper.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1896. Link to Illustration 10/1/21

New York City, Dept. of Sanitation and Street Cleaning, “Policeman, street cleaners. Two men hose down street, others with brooms. Boys watch. (nd) DORIS NY Link to Illustration Current 10/1/21

New York City, Department of Sanitation and Street Cleaning, “Street cleaners on loaded Gramm 6-ton truck. Two men in civilian dress in drivers seat; onlookers. Link to Illustration Current 10/1/21

Copyright Anne M. Filiaci 2020