By Anne M. Filiaci, Ph.D.

When Wald first arrived on the Lower East Side, she followed the lead of prominent reformers already at work in the neighborhood. Supporting their efforts, she acted to relieve neighborhood unemployment during the Panic of 1893, battled for housing reform, and successfully worked to create school and neighborhood playgrounds.

" order_by="sortorder" order_direction="ASC" returns="included" maximum_entity_count="500"]During the 1890s, Wald also became a fierce advocate in the fight to abolish child labor. In this effort too, she worked within the wider reform movement, informed by the beliefs of her mentors—most notably Jacob Schiff, Josephine Shaw Lowell and Jacob Riis –supplementing their actions with her own unique contributions.

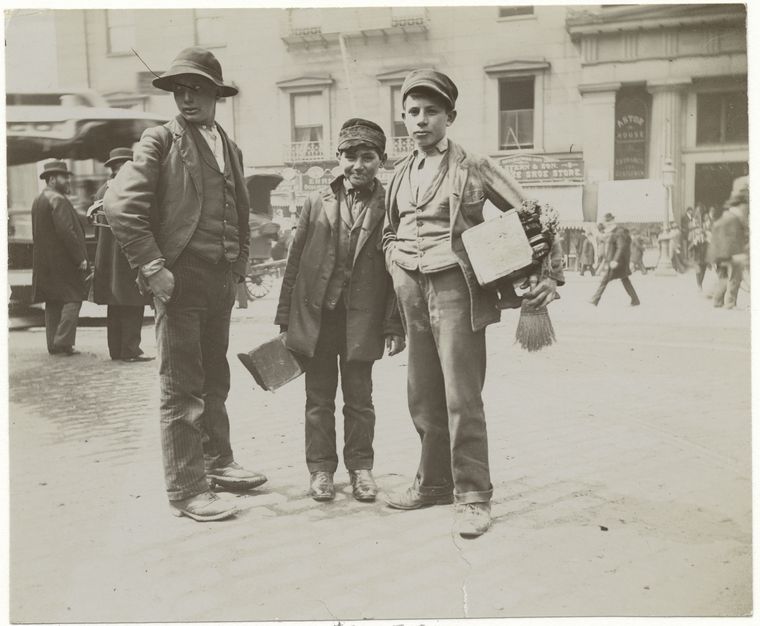

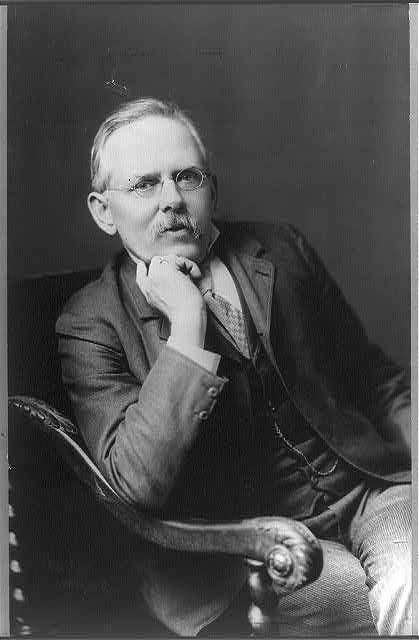

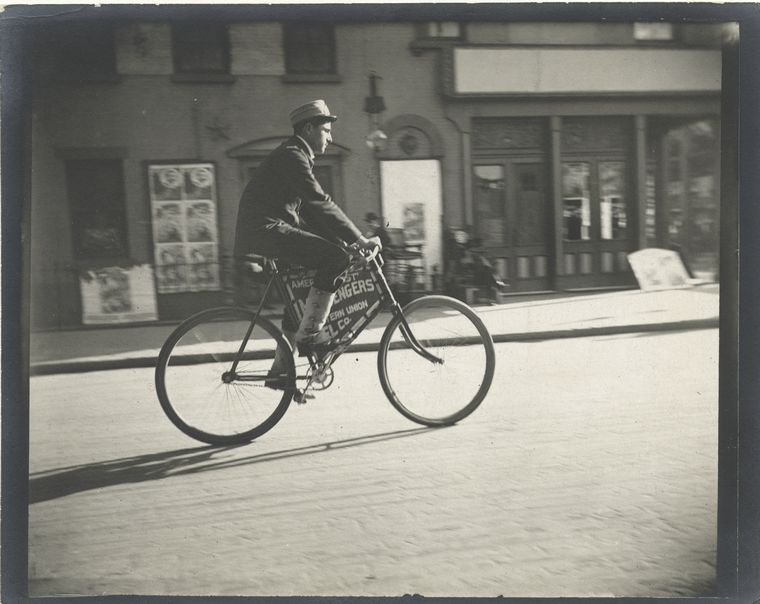

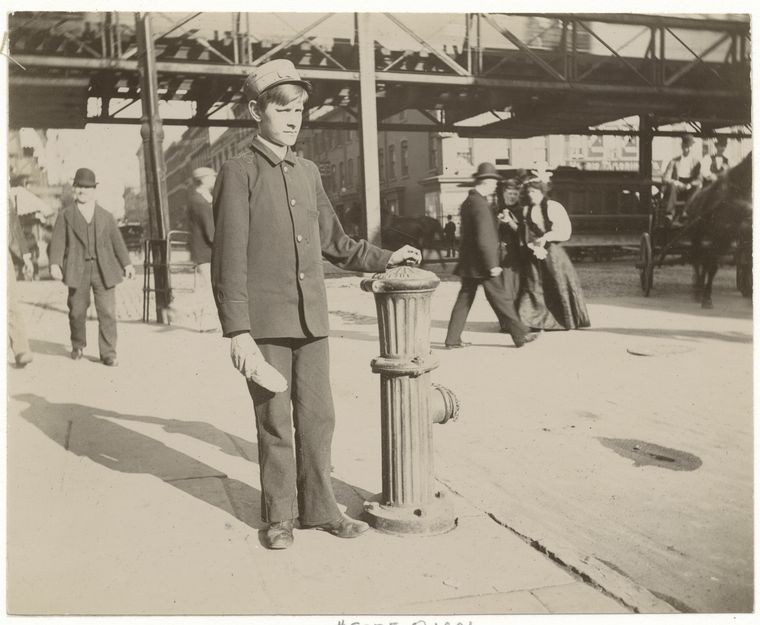

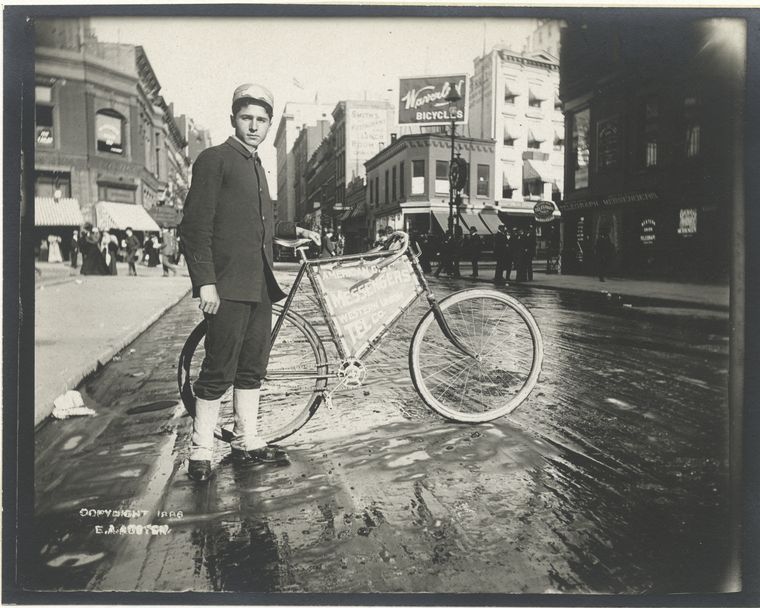

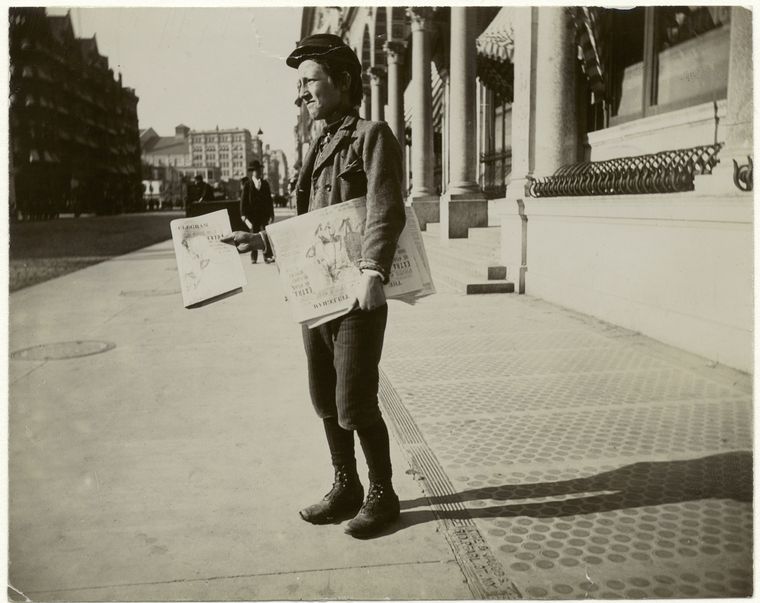

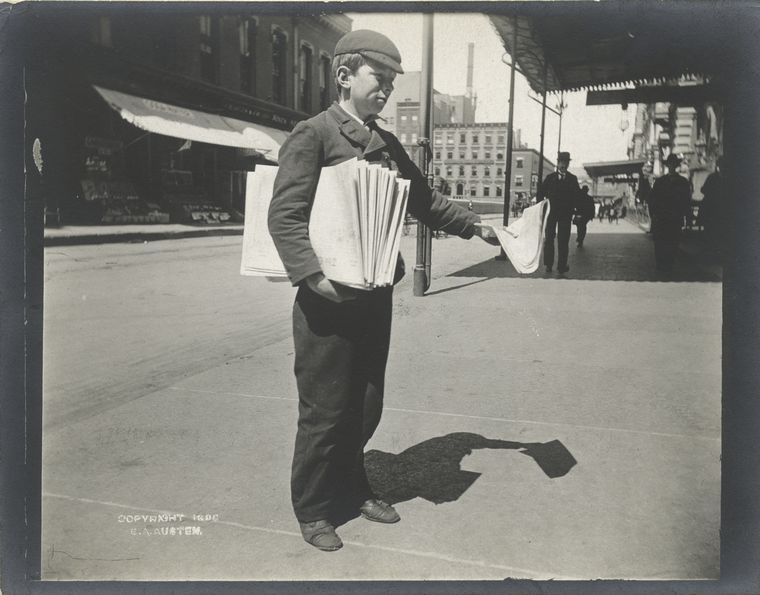

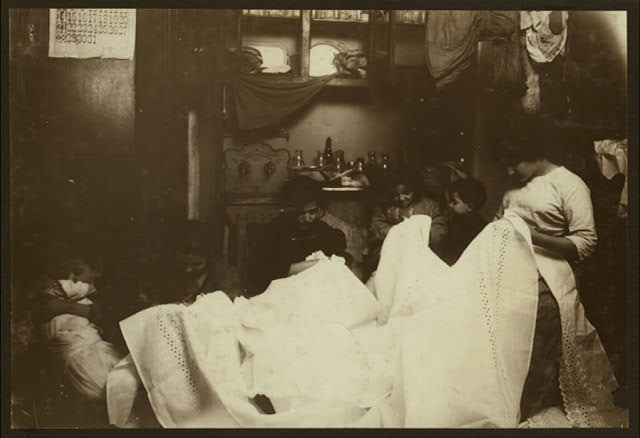

All three mentors had taken action to promote laws regulating child labor well before Wald moved into her new neighborhood. In the 1880s, Riis began to take photographs illustrating poverty in New York City. Initially displaying the pictures at his lectures and in magazine articles, he finally published them in his groundbreaking book How the Other Half Lives in 1890. In 1892, Riis published The Children of the Poor, continuing his popular practice of using anecdotes and photographs to depict the lives of impoverished children. This book included a whole section illustrating the evils of child labor in a variety of occupations. Riis focused on urban youngsters who toiled as factory workers, cash girls and boys in department stores, newsboys, messengers, wood gatherers, piece workers in tenement sweatshops, shoe shiners, peddlers, and “little mothers” (housekeepers and babysitters). He used stories about these children as well as vivid pictures of them at work to bolster his argument that anti-child labor laws already in existence were not only inadequate, but easily ignored.

Wald’s benefactor, Jacob Schiff, was a banker and most certainly not a radical labor rights agitator. But as a philanthropist he expressed concern for the plight of the poor, supported efforts to encourage upward mobility and advocated against unregulated child labor. In early 1893, Schiff lobbied the legislature in Albany in support of the “Ainsworth bill”—the Act to Regulate the Employment of Women and Children. This Act, written and introduced by the Working Women’s Society, proposed to extend factory legislation to cash girls and messenger boys, limiting the number of hours that these minors could work. Schiff’s April 1893 letter to the chair of the New York State Assembly’s Committee on Labor and Industry declared that “‘all our efforts’” to improve “‘both the moral and actual status’” of the poor “‘must come to naught, if such legislation… cannot be had.’” (Adler)

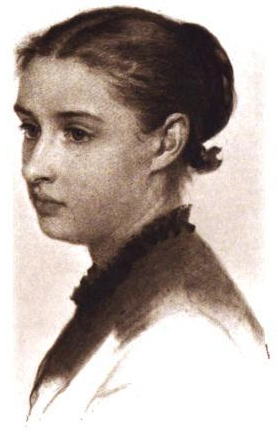

Philanthropist Josephine Shaw Lowell, another early mentor and friend of Wald, was instrumental in creating the Working Women’s Society (WWS), the group that wrote the Ainsworth bill supported by Schiff. Shaw Lowell also served as the first president of a spin-off group of the WWS, the Consumers League of New York. A prominent and steadfast reform advocate and lobbyist, Lowell traveled to Albany in 1895 to argue in support of legislation limiting and regulating child labor. Her testimony is credited with helping to pass the Mercantile Inspection Act in 1896, a law that set a maximum work limit of sixty hours per week for shop girls in towns with more than 3,000 people. The law also required employers to provide seats for women employees in shops. (Waugh, Lubove)

Wald’s mentors, friends and allies also pushed successfully for the passage of the Compulsory Education Law of 1894. This law limited child labor by requiring full-time school attendance for children between eight and twelve years old. It also required children between the ages of twelve and fourteen to obtain a work permit, and mandated that they attend school for eighty consecutive school days in a year in order to qualify. The law directed large cities in New York State to take a biennial census of all children between the ages of five and eighteen, thus making it easier for reformers to track how many children should be attending school, who they were and where they lived. (Stambler)

Initially a follower rather than a leader, Wald used personal charisma, a considerable gift for empathy and an engaging attitude to extend her influence with both reform leaders and neighbors. She listened to benefactors and philanthropists, incorporating their ideas, taking in their adult children as interns, remembering their birthdays and keeping them informed about her work. Wald also brought much needed nursing skills to the community, exuding warmth, sympathy and empathy with her patients, often stating that it was not her job to judge them but rather to understand and to speak for them. Her skills and personality soon granted her not only access to the houses of the poor, but their trust and friendship.

Perhaps most importantly, when Wald and the other Henry Street nurses visited neighborhood tenements, they halted or slowed the spread of diseases, watched over children, tended infants, sat with the ill, cleaned rooms, brought fresh curtains and linens into homes (and sometimes flowers), and provided not only medicine but healthy food and drink. In short, Wald and her nurses were responsible for measurably improving the quality of their patients’ lives, keeping them healthy and helping them to live longer.

In nursing school, Wald had learned how to objectively observe and report to doctors on the status of patients. This skill served her well not only as a nurse but as a social services investigator. Prominent reformers increasingly relied on her to collect data and to provide testimony relaying hard information and anecdotal eyewitness accounts about the everyday lives of her neighbors.

Like many reformers, Wald came to believe that the sweatshop system was central to the problem of public health in general and child labor in particular. As long as tenement shops existed, she reasoned, child labor could not be effectively outlawed. She wrote that when “work is carried on in the home all members of the family can be and are utilized without regard to age….” (Wald, House…) Reformers regularly used Wald’s first-hand observations to support their assertions that tenement sweatshops thwarted attempts to curtail child labor. Wald provided eyewitness accounts that parents not only made their children work in home sweatshops outside of school hours—she also saw families who commonly undermined compulsory education laws by keeping their children out of school in order to make money at home.

Wald provided anecdotes, as well as data. She wrote of “Josephine, eleven years of age,” who

“stays out of school to work on finishing; Francesca, aged twelve, to sew buttons on coats, Santa, nine years old, to pick out nut meats; Catherine, eight years old, sews on tags; Tiffy, another eight-year-old, helps her mother finish; Giuseppe, aged ten, is a deft worker on artificial flowers.” (Wald House)

Wald often told a story of one child who showed up asking “for help to the nurse in the First Aid Room at the settlement.” His appearance led her to discover that he was one of “a family of [five] pathetic children, pasting paper bags in a chilly basement room.” None of these children—all of whom had been born in America—had ever been to school. The other children in the neighborhood had not even known of their existence, because “‘they never came out to play.’” (Wald, House…, Windows…)

Since Wald was a nurse, it was logical that many of her stories centered on the public health hazards of the sweatshop. In her daily work, she often came across people making clothing, cigarettes, and other goods while suffering from contagious diseases like measles, tuberculosis, diphtheria and scarlet fever. In those early days, she saw, with “no little consternation…toys and infants’ clothing, and sometimes food itself, made under conditions that would not have been tolerated in factories, even at that time.” (Wald, House…) This, she pointed out effectively, was a public health risk not only for tenement inhabitants, but for the more prosperous Americans who bought the products made in these workplaces. As she so vividly put it,

“…we saw a roomful of children’s clothing shipped to the Southern trade from a tenement where there were sixteen cases of measles. One of our patients, in an advanced stage of tuberculosis,…sat coughing in her bed, making cigarettes and moistening the paper with her lips.” (Wald, House…)

In another “nearby” tenement, Wald watched as “parents worked as finishers of women’s cloaks of good quality” while their children lay, “ill with scarlet fever” on the bed underneath the garments. (Wald, House…) Summing up her efforts to educate the wider public during those early years, Wald later wrote,

We gave such publicity as was in our power to the conditions we found, not disdaining to stir emotionally by our ‘stories’ when dry and impersonal statistics failed to impress.” (Wald, House…)

In addition to publicizing the evils of tenement sweatshops, Wald also used her nursing skills more directly to get children out of the workplace and into the classroom. Since unvaccinated children were not allowed in school, she early on obtained “virus points and authority to vaccinate” from the Department of Health, then vaccinated school-age children during visits to their homes. She and her nurses also set about remedying minor contagious diseases that excluded children from school—diseases like head lice, eczema, scabies, ringworm, etc. (Duffus)

Within a few years, Wald was no longer simply supporting the work of her mentors; she had become a recognized reform leader. As the Henry Street Settlement grew, Wald increasingly relied on resident nurses as investigators, encouraging them to report on sweatshop conditions and using their stories in her own testimony and in other forms of advocacy. (Daniels)

By the end of the 1890s, Wald’s prominence in the field of reform, including child labor reform, had become recognized to the point where she was often called to testify before commissions, boards, and committees. In 1898, she was elected to serve on the Board of Governors of the influential Consumers’ League of New York. (“Consumers League Work”) The next year found her lobbying Teddy Roosevelt, urging him to hire Florence Kelley. Kelley, an anti-child labor advocate, had lost her position as Illinois’ factory inspector when her employer, governor John Altgeld, lost his re-election effort. Although Wald did not succeed in getting Kelley the New York government job (in part because Roosevelt was a political adversary of Altgeld), Kelley did become Executive Secretary for the National Consumers League—and a long-term resident of the Henry Street Settlement.

Bibliography

Adler, Cyrus, Jacob H. Schiff: His Life and Letters, Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Doran and Co., Inc., 1929, vols. I & II (Vol. I, pp. 295-296).

Blumberg, Dorothy Rose, Florence Kelley: The Making of a Social Pioneer, New York: Augustus M. Kelley, 1966 (p. 115).

Bradbury, Dorothy E., Four Decades of Action for Children; a short history of the Children’s Bureau, Dorothy E. Bradbury, Assistant Director, Division of Reports, Children’s Bureau, To the Future, Martha M. Eliot, M.D., Chief Children’s Bureau; U. S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Social Security Administration; Children’s Bureau, For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D. C., 1956. (Preface).

Carson, Mina, Settlement Folk: Social Thought and the American Settlement Movement, 1885-1930, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990.

Cohen, Naomi W., Jacob H. Schiff: A Study in American Jewish Leadership, Hanover, NH: Brandeis University Press, 1999 (pp. 29-30, 95).

“Consumers’ League Work,” New York Times, January 22, 1898.

Daniels, Doris Groshen, Always a Sister: The Feminism of Lillian D. Wald, New York, Feminist Press, 1989 (pp. 105-106).

Davis, Allen F., Spearheads for Reform: The Social Settlements and the Progressive Movement, 1890-1914, New York, Oxford University Press, 1967.

Duffus, R.L., Lillian Wald: Neighbor and Crusader, New York: The Macmillan Company, 1939 (p. 74).

Kelley, Florence, Some Ethical Gains Through Legislation, by Florence Kelley, New York: The Macmillan Company, 1905 (p. 240)

[Kelley] Wischnewetzky, Florence Kelley, Our Toiling Children, Chicago, Women’s Temperance Publication Association, 1889 At http://florencekelley.northwestern.edu/archives/kelley/ Current 5/8/2019

Kelley, Florence, Secretary, “Report from the National Consumers’ League.” Reports from State and Local Child Labor Committees and Consumers’ Leagues, Florence Kelley, Secretary.” Reports from State and Local Child Labor Committees and Consumers’ Leagues, George Hall, Arthur O. Lovejoy, Henry J. Harris, H. Wirt Steele, Edward W. Frost, Scott Nearing, I. A. Loos, C. B. Wilmer, Benjamin J. Baldwin, Charles L. Cone, A. J. McKelway, Millie R. Trumbull, Phebe T. Sutliff, A. M. Beardsley, Florence L. Sanville, Daniel Miller, Edith M. Howes, Florence G. Taylor, Catharine Avery, Geraldine Gordon, Florence Kelley and Samuel McCune Lindsay, Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science , Vol. 29, Child Labor (Jan., 1907), pp. 142-183 Published by: Sage Publications, Inc. in association with the American Academy of Political and Social Science (p. 178-179).

Lane, James B., Jacob A. Riis and The American City, Port Washington, NY: Kennikat Press, 1974 (pp. 135-136).

“Lillian D. Wald: 1860-1940,” Social Service Review, v. 14, no. 4, (Dec. 1940) pp. 755-757.

Lindenmeyer, Kriste, “A Right to Childhood”: The U.S. Children’s Bureau and Child Welfare, 1912-46 Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1997.

Lubove, Roy, The Progressives and the Slums: Tenement House Reform in New York City, 1890-1917, np: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1962 (p. 208).

Muncy, Robyn, Creating a Female Dominion in American Reform, 1890-1935, New York: Oxford University Press, 1991 (p. 35).

Riis, Jacob, The Children of the Poor, New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1908 (c1892) http://archive.org/stream/childrenofpoor00riisuoft#page/20/mode/2up (openlibrary.org) Current 5/8/19.

Riis, Jacob, How the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York, New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1890 https://books.google.com/books?id=zhcv_oA5dwgC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false Current 6/19/19.

Stambler, Moses, “The Effect of Compulsory Education and Child Labor Laws on High School Attendance in New York City, 1898-1917”, Source: History of Education Quarterly, Vol. 8, No. 2 (Summer, 1968), pp. 189-214 (see especially pp. 190-191, 194-195).

Trattner, Walter I., Crusade for the Children: A History of the National Child Labor Committee and Child Labor Reform in America, Chicago: Quadrangle Books, 1970 (p. 28-29).

Wald, Lillian, “Child Labor,” Lillian D. Wald, The American Journal of Nursing, Vol. 6, No. 6 (Mar., 1906), pp. 366-369.

Wald, Lillian D., The House on Henry Street, NY: Henry Holt & Co., 1915 (HHS, p. 114, pp. 152-156).

Wald, Lillian D., Windows on Henry Street, Boston: Little Brown, and Company, 1934 (WHS, pp. 195-196).

Waugh, Joan, Unsentimental Reformer: The Life of Josephine Shaw Lowell, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1997 (pp. 199-200).

Woods, Robert A. and Albert J. Kennedy, The Settlement Horizon: A National Estimate, New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1922 (p. 381).

Illustrations

Hine, Lewis Wickes, photographer.

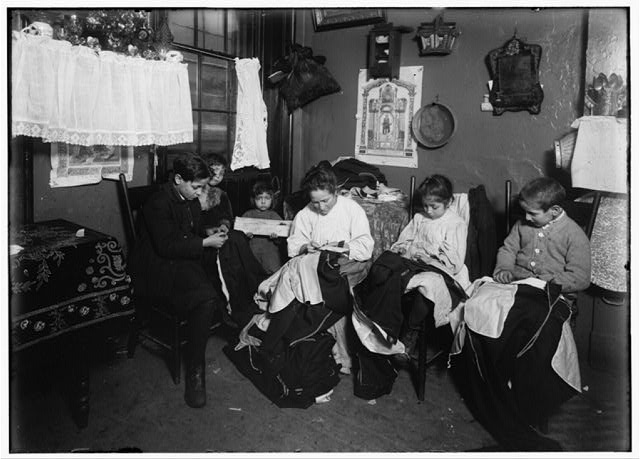

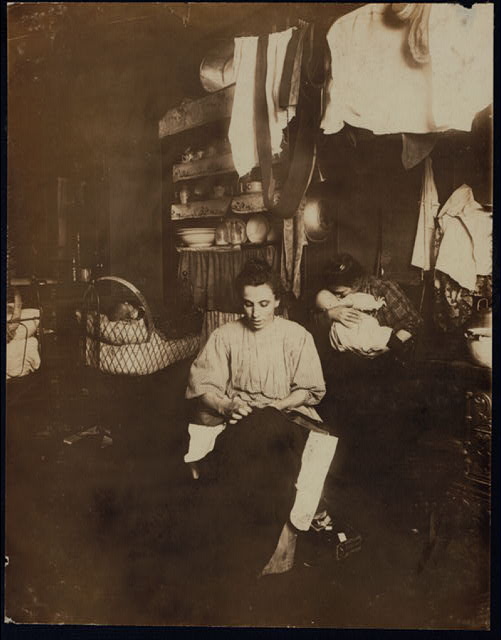

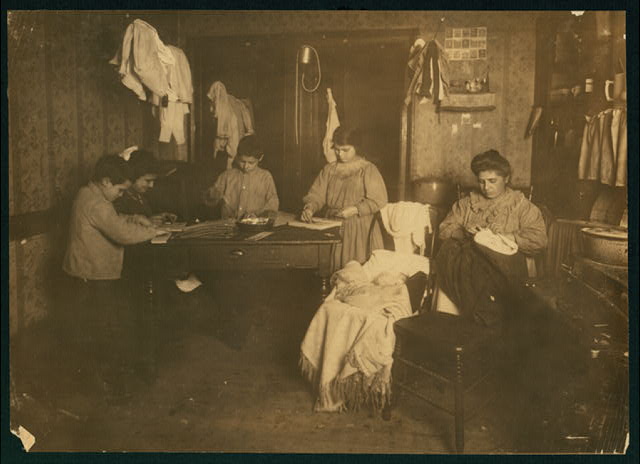

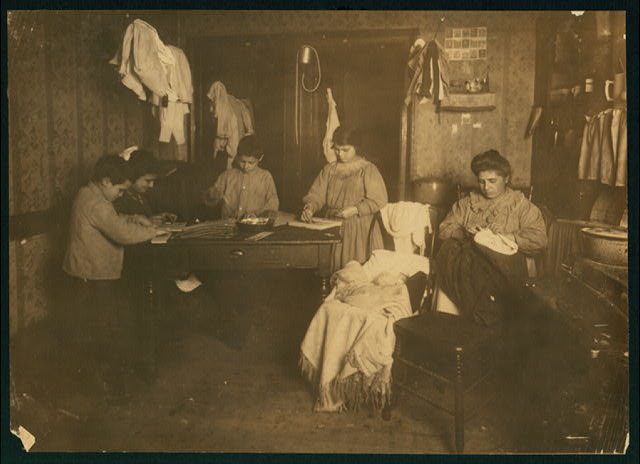

(These photos were taken after the period covered in the essay above. However, they often accurately depict the situation described by Wald during the 1890s.)

Hine, Lewis Wickes, photographer. [1 P.M. Family of Onofrio Cottone, 7 Extra Pl., N.Y., finishing garments in a terribly run down tenement. The father works on the street. The three oldest children help the mother on garments. Joseph, 14, Andrew, 10, Rosie, 7, and all together they make about $2 a week when work is plenty. There are two babies.Location: New York, New York State]. January, 1913. Image. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, Link to Illustration Current 8/29/19

Hine, Lewis Wickes, photographer. [Mrs. Tony Racioppo, 260 Elizabeth St., N.Y. 1st floor rear, finishing pants in dirty tenement home. Although it is a licensed house, the whole place is very much run down. The ahllway i.e., hallway is in the same condition as that one at 266 Elizabeth see photo. Baby had bad cough. Mother said recovering from measles.Location: New York, New York State]. February, 1912. Image. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, Link to Illustration Current 8/29/19

Hine, Lewis Wickes, photographer. 6 P.M. Callabria family, 647 E. 12th St., N.Y. see schedule Mother finishes clothing. The children paste needle packages onto cards and said they all work at times until 10 or 11 P.M. They are 9, 12, 14 and 15 years old and all go to school. They are undersized. The baby in the cart is one month old. Location: New York, New York State. February, 1912. Image. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, Link to Illustration Current 8/29/19

Hine, Lewis Wickes, photographer. Cutting out embroidery on the dirty kitchen floor. Battista family, 259 E. 151 St. N.Y. On the right is the married daughter, who lives down stairs and usually works there. On her right next to the boy is Flora, said to be 9 years old and very much stunted in size. “Been sick.” Next to her is the mother and next is Linda, 11 years old. The baby, dirty and covered with sores, was being handed about. Probably has impetego. Location: New York, New York State. January, 1912. Image. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, Link to Illustration Current8/29/19

Medium: 1 photographic print. Reproduction Number: LC-DIG-nclc-03422 (color digital file from b&w original print) Rights Advisory: No known restrictions on publication. For information see: “National Child Labor Committee (Lewis Hine photographs),” https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/res.097.hine Access Advisory: For reference access, please use the digital item to preserve the fragile original item. Call Number: LOT 7480, v. 1, no. 1252 [P&P] Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print Link to Illustration Current 8/29/19 Hundreds of pictures of child labor included in this link. Title: Miscellaneous child labor in the United States Creator(s): Hine, Lewis Wickes, 1874-1940, photographer Related Names: National Child Labor Committee (U.S.) , funder/sponsor Date Created/Published: 1908-1924. Medium: 3 albums (811 photographic prints) ; 27 x 30 cm. (album) Summary: Photographs show child labor in a variety of trades: furniture manufacturing, lumber industry, marble polishing, basket and broom manufacturing, shoe industry, meat packing, cigar and cigarette making, candy making and service work in department stores, ice cream parlors, pool halls, and bowling alleys. A few images of child vaudeville performers are also included. In many cases, workers are shown going to or coming from work or collecting pay, rather than engaging in work activities. Procedures intended to regulate labor practices, such as obtaining work certificates, are included. Images documenting work-related injuries and health care activities are included, as are a few “posture photos.” Also shown are children scavenging for food and fuel and informal recreational activities, including boys playing craps on streets, “hanging around,” and leaping on streetcars. Activities offered by boys’ clubs and settlement houses, and playground activities, including baseball, are also featured. Schools, particularly for immigrants, and vocational education activities are depicted. Also included are a substantial number of exhibit panels dealing with labor issues–a few show actual exhibit installations; some exhibit objects and cartoons; as well as portraits of officials of the National Child Labor Committee, including Owen Lovejoy and Jane Addams, and groups of female factory inspectors. Locations represented include: Alabama; Connecticut; Delaware; Florida; Indiana; Kentucky; Massachusetts; Michigan (1 image); Missouri; New York; North Carolina; Oklahoma; Rhode Island; Texas; Vermont; Virginia; Washington, D.C. Reproduction Number: — Rights Advisory: No known restrictions on publication. Access Advisory: For reference access, please use the digital images in the online catalog to preserve the fragile original items Call Number: LOT 7483 (F) (M) (Use Digital Images) [P&P] Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA Link to Illustration Current 8/29/19 Josephine Shaw Lowell Wikipedia images, public domain Link to Illustration Current 8/28/19 Link to Illustration Current 8/28/19’ The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography Vol. 8 Published by J.T. White, p. 142 (1898). Link to Illustration Current 8/28/19 The Philanthropic Work of Josephine Shaw Lowell By William Rhinelander Stewart by A. St Gaudens, Link to Illustration Current 8/28/19 Source: English: The Philanthropic Work of Josephine Shaw Lowell: Containing a Biographical Sketch of Her Life, Together with a Selection of Her Public Papers and Private Letters, Collected and Arranged for Publication By William Rhinelander Stewart Published by The Macmillan company, 1911 page 48, Link to Illustration current 8/28/19 New York Public Library Photograph Collections The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. “Messenger boy” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1896. Link to Illustration Current 8/28/19 The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. “Messenger.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1896. Link to Illustration Current 8/28/19 The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. “Newsgirl” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1896. Link to Illustration Current 8/28/19 The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. “Peddler, shoe strings.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1896. Link to Illustration Current 8/28/19 The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. “Messenger boy.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1896. Link to Illustration Current 8/28/19 The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. “Bootblacks, City Hall Park, NYC.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1896. Link to Illustration Current 8/28/19 The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. “Newsboys.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1896. Link to Illustration Current 8/28/19 The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. “Newsboy.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1896. Link to Illustration Current 8/28/19 The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. “Bootblacks.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1896. Link to Illustration Current 8/28/19 The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. “Bootblack.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1896. Link to Illustration Current 8/28/19 The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. “Bootblacks.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1896. Link to Illustration Current 8/28/19 The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. “Newsboy.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1896. Link to Illustration Current 8/28/19 The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. “Messenger.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1896. Link to Illustration Current 8/28/19 Jacob Riis “Family making artificial flowers,” by Jacob Riis, c. 1890 CE. http://www.college.columbia.edu/core/content/%E2%80%9Cfamily-making-artificial-flowers%E2%80%9D-jacob-riis-c-1890-ce or for image only Link to Illustration Current 8/29/19 Riis, Jacob, Jacob Riis (no known restrictions on publication); c1904 April 1. Digital ID: (b&w film copy neg.) cph 3a08818 http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3a08818; Reproduction Number: LC-USZ62-5511 (b&w film copy neg.); Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA Link to Illustration Current 8/29/19 Riis, Jacob, Jacob Riis, American journalist. 1905. Public domain. Link to Illustration Current 8/29/19 Riis, Jacob, NYC Police Commissioner Roosevelt walks the beat with journalist Jacob Riis in 1894—Illustration from Riis’ autobiography. Public domain. See also, Roosevelt, Theodore. Link to Illustration Current 8/29/19 See the following links for electronic copies of Riis’s books, including illustrations: Riis, Jacob, The Children of the Poor, New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1908 (c1892) (Wald9, Riis, Children of the Poor) ttp://archive.org/stream/childrenofpoor00riisuoft#page/20/mode/2up (openlibrary.org) Current 8/29/19 Riis, Jacob, How the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York, New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1890. Several fulltext copies online, including Link to Illustration , Current 8/29/19 Digitization of photos in Riis, Jacob, How the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York at PetaPixel. (“Established in May of 2009, PetaPixel is a leading blog covering the wonderful world of photography. Our goal is to inform, educate, and inspire in all things photography-related.” Link to Illustration current 8/29/19 Also see results from Google Images search, “how the other half lives,” Link to Illustration current 8/29/19 “Jacob A. Riis’s New York,” slide show by New York Times, at Link to Illustration current 8/29/19 (Subscription needed) Jacob Schiff Title: Jacob Schiff & wife Creator(s): Bain News Service, publisher Date Created/Published: [no date recorded on caption card] Medium: 1 negative : glass ; 5 x 7 in. or smaller. Reproduction Number: LC-DIG-ggbain-30017 (digital file from original negative) Rights Advisory: No known restrictions on publication. Call Number: LC-B2- 5122-3 [P&P] Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA Link to Illustration Record: Link to Illustration Larger image: Link to Illustration Current 8/29/19 Image Title : Jacob H. Schiff, Kuhn, Loeb & Co. Source : Print Collection portrait file. / S / Jacob H. Schiff. Location : Stephen A. Schwarzman Building / Print Collection, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs Digital ID : 2054988 Record ID : 1959462 Digital Item Published : 9-2-2011; updated 1-24-2012 NYPL Image: Link to Illustration Current 8/29/19 Miscellaneous Girls Sew Link to Illustration Current 8/29/19 Copyright Anne M. Filiaci 2021