By Anne M. Filiaci, Ph.D.

The First Club

Wald called the Henry Street Settlement’s first boys’ club a “happy accident.” It arose out of “an extremely unpleasant encounter with boys who were suspicious of strangers [i.e., settlement workers].” The New York Times later called these boys part of a “‘young gang’ who had been making nuisances of themselves in the Settlement neighborhood.” Their behavior included throwing “decaying vegetables at the nurses,” who they thought were “missionaries.”

" order_by="sortorder" order_direction="ASC" returns="included" maximum_entity_count="500"]The boys, eleven and twelve years old, had reached an age when “the average boy” on the Lower East Side tended “to run with a gang.” Yet instead of turning the unruly pre-adolescents over to the police or banning them from the Settlement, Wald welcomed them when they showed up at her door one day in the summer of 1895 and asked to see her when she “wasn’t busy.” She made an appointment with them for “the next Saturday evening,” and when the boys returned she helped them to form the American Heroes Club.

The mission of the American Heroes Club was to study individuals who “had contributed to the betterment of America.” This, according to Wald, “opened up a wide selection of artists, writers, pioneers, civil servants, scientists, Presidents” and “military men.”

Those who joined the club—and all Settlement clubs that followed—formalized their group with a constitution that outlined members’ rights and the duties. In keeping with Wald’s oft-repeated maxim that “good manners are minor morals,” club members agreed to respect one another and to be considerate of the needs and feelings of all.

When the boys had, according to their president, “run out of American heroes,” they studied civics and became active in local reform campaigns as messengers, “soap-box orators” and “distributors of campaign literature.” Their political activism first emerged during Seth Low’s reform election for mayor of New York City in 1897. About a decade later, one settlement resident fondly recalled

Miss Wald in blue-checked dress giving final instruction to her corps of assistants, and sending them forth with their printed sheets…to help secure a clean mayoralty for our great city.

The American Heroes Club had study, discussion, and (later) political activism as its central goals. Yet Wald made sure that when the boys met they also got physical activity and “good times.” “The “programmes of the very earliest clubs,” Wald said, “always left time for fun,” whether it was sleigh rides, or trips to the theater, or hikes and baseball, or “just a party.”

Other Clubs

The Henry Street Settlement soon became host to a variety of other clubs. Eventually it was able to offer a gymnasium, where boys participated in a number of athletic clubs and team sports. These athletic activities became such an important a part of the Settlement’s mission that when the “Nurses’ Settlement” changed its name to the Henry Street Settlement, it was in part because their teams were often “taunted” with derisive chants of “Noices! Noices!”

The neighborhood’s married women also found a place in the Settlement. Often women’s clubs* gave immigrant women a chance to socialize and an excuse to get out of their homes and to better assimilate by learning the customs and culture of their adopted country. Nurse resident Lavinia Dock describes their activities:

One nurse, skilled in the Yiddish dialect, teaches a class of foreign-born mothers in simple home nursing and hygiene. These are the poorest and most hard worked of women, who have had the scantiest portion of the world’s advantages. They have come from Russia too late in life to learn English . . . They come weekly to their class, and after the lesson is over the samovar is placed upon the table and they drink tea. Visitors come in sometimes to sing and play, and reminiscences of Russian songs and folk-lore are revived in their minds. This lasts all through the winter, and in the summer the social part is continued in the garden.

Residents of the Henry Street Settlement conducted a similar class/club for

English-speaking mothers, conducted on the same lines, and, after they have had the nursing course, there follows a series of cooking lessons in the big, old-fashioned kitchen of the second house, where they sit down to a cozy, clean table with the prettiest of cheap dishes for object lessons, and enjoy the simple, well-cooked food made from the least expensive materials, and designed to show them how for the same amount of money that they themselves might spend they can prepare dishes more attractive and toothsome than they usually have. These mothers are also of the very poor, though with more hope and aspirations than those who speak no English. They dearly love their classes, and call themselves the G.T.C., the Good Times Club.

Structure

Wald made sure that the Settlement was a place that not only aided and welcomed her neighbors, but also a refuge of calm and beauty in the midst of the dirt and chaos of the Lower East Side. She insisted on providing visitors to the Settlement with a pleasing environment. “Shabby rooms,” she said, “are never economical when measured by results. Meticulous cleanliness, flowers,” and “good pictures,” to her, were “essential.”

During the Settlement’s early years, it was mainly nurses who ran the clubs, classes and activities. Since this was generally done after their normal daily routine of visiting and treating patients, this soon proved too much of a burden, and Wald began to recruit non-nurse residents and volunteers to conduct some of the Settlement’s social activities. Eventually these became almost solely the work of non-nurse residents and volunteers.

While the nurse residents and lay members of the House on Henry Street remained mostly female, Wald soon realized that in order to attract and keep boys and young men in clubs and activities she would need male residents and volunteers. Many of the young (usually college-aged) men that she subsequently recruited to lead the Settlement’s clubs, sports and other activities later became city, state and national leaders. One was Raymond Fosdick, a starving law student who led clubs in exchange for a room at HSS. He later became an advisor to the mayor of New York and to President Wilson. Another, Graham Wallas, was a leader of the British Fabian Socialists and a founder of the London School of Economics. Herbert Lehman was a Henry Street Settlement club leader before he went on to become a Senator and the Governor of New York State, while Henry Morganthau, Jr., another HSS alumnus, served as Secretary of the Treasury under Franklin Delano Roosevelt. In addition to these more illustrious club leaders, many men who had grown up as club members, appreciative of these formative experiences, returned as young men to lead the clubs to which they had once belonged.

Conclusion

By 1902, Wald could boast that there were “now thirty-five clubs which have grown up one by one as parts of the social life of the settlement.” She later wrote of the lifelong friendships formed in clubs, and the enduring loyalty both to their fellow club members, to the principles they learned and to the Settlement itself. Of the American Heroes Club, she wrote that after fifteen years

They still are devoted to each other and to us, and constitute in practically every instance, a real contribution to the good citizenship of the city. Some of them are married and have named their babies after me. They are all doing well in their various occupations and have comfortable little homes of their own with a very high standard of domestic and patriotic duties. A number of them are helping us in our club and social work and can be counted upon as real sons of the house.

And years later, Wald was proud to write that the thirty-fifth anniversary” gathering of the Settlement’s first women’s club “produced a gathering of about a hundred women, among them all but one of the original group.” The years had transformed the original ragtag group into “a meeting of sophisticates.” Yet Wald was happy to notice that their upward mobility

did not in the least lessen the emotional warmth, the long reminiscences of what had been and of what they felt they had gained through their association with one another and with the Settlement.

Notes

*“A Mother’s Club was formed in order to give women a chance to expand their interests and to learn the things that their children and husbands absorbed outside of the home. It is interesting to note that Wald, while she endorsed the idea of the club, hated its name. She wrote to the man in charge of these groups: ‘Thank you for all the various reports. And please dig someone for insisting on calling the Women’s Clubs, Mother’s Clubs! I notice in the Board Delegates Meetings that every reference is to the Mother’s Clubs. You know my sentiments about the right of a woman to be something besides a mother.’” [Wald to Karl Hesley, 5 December 1932, NYPL, Wald MSS.] Always a Sister, Daniels, p. 45.

Bibliography

Carson, Mina, Settlement Folk: Social Thought and the American Settlement Movement, 1885-1930, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990.

Daniels, Doris Groshen, Always a Sister: The Feminism of Lillian D. Wald, New York, Feminist Press, 1989.

Davis, Allen F., Spearheads for Reform: The Social Settlements and the Progressive Movement, 1890-1914, New York, Oxford University Press, 1967.

Duffus, R.L., Lillian Wald: Neighbor and Crusader, New York: The Macmillan Company, 1939.

[Epstein], Beryl Williams, Lillian Wald: Angel of Henry Street [author’s name on title page is “Beryl Williams”], NewYork: Julian Messner, Inc., 1948.

Feld, Marjorie N., Lillian Wald: A Biography, Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2009.

Fosdick, Raymond B., Chronicle of a Generation: An Autobiography, New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1958.

Holden, Arthur C., The Settlement Idea: A Vision of Social Justice, New York: The Macmillan Co., 1922.

“Lillian Wald Dies; Friend of the Poor,” New York Times, Sept 2, 1940.

“Official Reports of Societies,” The American Journal of Nursing, Vol. 2, No. 5 (Feb., 1902), pp. 377-388.

Simkhovitch, Mary Kingsbury, The Settlement Primer, [np]: National Federation of Settlements, Inc., 1936 (2nd ed.; 1st ed. 1926).

Wald, Lillian D., The House on Henry Street, New York: Henry Holt & Co., 1915.

Wald, Lillian, Lillian Wald Papers, New York: New York Public Library, [1983].

Wald, Lillian D., Windows on Henry Street, Boston: Little Brown, and Company, 1934.

Illustrations

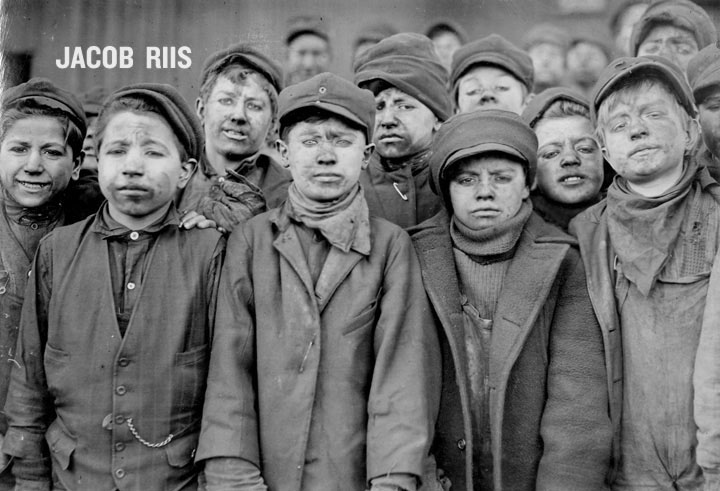

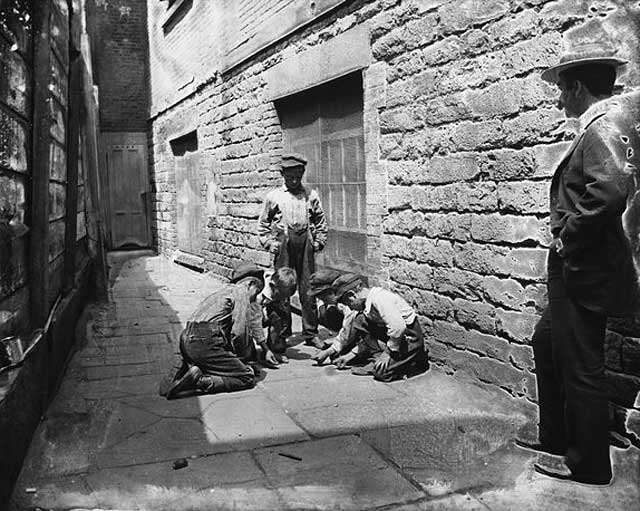

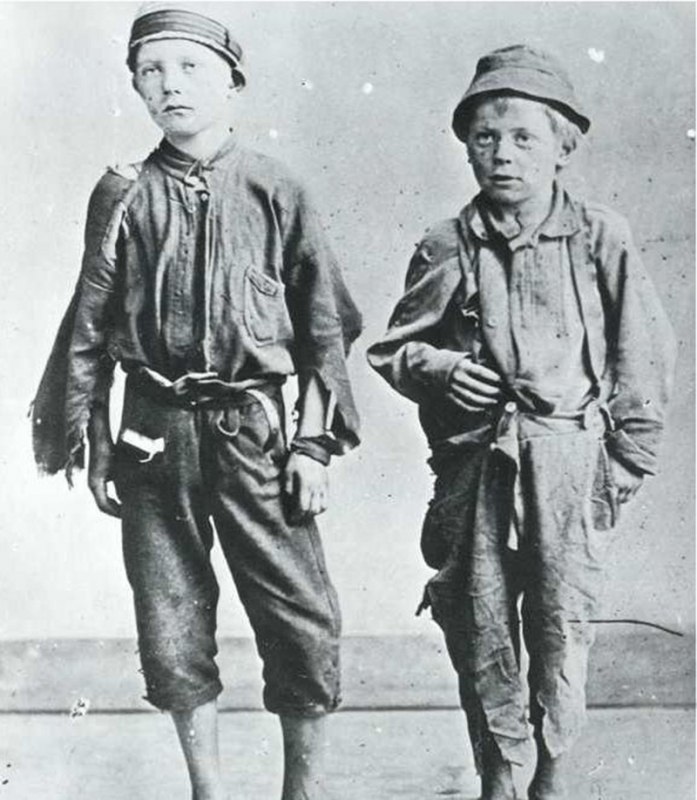

Images of young boys in NY—Google Images search terms: jacob riis how the other half lives photo gallery street arabs

Scene in tenement, 1890 Link to Illustration (Current 5/25/16)

Street arabs, 1890 Link to Illustration (Current 5/25/16)

Shooting craps, playing in the street,1890 Link to Illustration (Current 5/25/16)

Boys, untitled (haunting) 1890 Link to Illustration (Current 5/26/16)

Two boys, untitled, ca. 1890 Link to Illustration (Current 5/26/16)

Images in NY—Google Images search terms: Jacob riis children of the poor

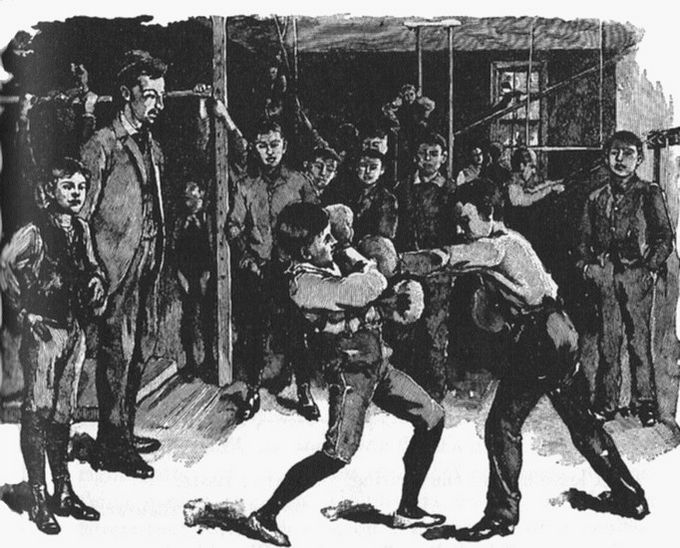

A bout with the gloves in the boys’ club of calvary parish”, 1892, Children of the poor. p.235 Link to Illustration (Current 5/26/16)

Girls, Children of the Poor, 1892 Link to Illustration (Current 5/26/16)

Copyright Anne M. Filiaci 2016