GOOD INTENTIONS PAVE THE ROAD TO HELL—

MEDICAL EXAMINERS DEPOPULATE THE SCHOOLS

When Wald moved to the Lower East Side, unhealthy poor children often lacked access to even the most basic education. Some, “too weak or ill,” could not attend “school regularly,” while teachers sent home others who had contagious but “easily remedied defects” —mainly head lice and minor skin diseases. To make matters worse, “a more or less constant though far from negligible” group of contagious children managed to fly under radar, attending school and spreading ailments to their healthy classmates.

In order to illustrate the problem, Wald often told the story of Louis, whom she met when she “had been downtown only a short time.” For years Louis had been unable to attend classes because he had scalp eczema—a minor and curable ailment. Although he “had been to the dispensary a good many times,” he apparently did not understand how to use the medicine they gave him, and the eczema persisted. When Wald sought out his mother, she found a thoroughly overworked woman standing “over a washtub, a fretting baby on her left arm, while with her right she rubbed at the butchers’ aprons which she washed for a living.”

Any nurturing skills Louis’s mother may have possessed were diminished by her burdens. Blaming her son for his predicament, she called Louis “‘bad’” because he “did not ‘cure his head.’” Louis, meanwhile, hung “the offending head” in shame, saying that “he knew it was awful for a twelve-year-old by not to know how to read the names of the streets on the lamp-posts.” He lamented that “every time I go to school Teacher tells me to go home.”

Wald examined and treated Louis’s head, soon curing the eczema with an “intelligent application” of ointment from the dispensary. The next September, she “had the joy of securing the boy’s admittance to school for the first time in his life.” Evidence of success was immediate—the “next day, at noon recess,” Louis “fairly rushed up” the “five flights of stairs” to Wald’s “Jefferson Street tenement,” where he proceeded “to spell the elementary words he had acquired that morning.”

Louis, Wald said, “set” her “thinking” about what she could do to keep children in school. His problem—and its fairly simple remedy—inspired her and Mary Brewster to collect and keep data on children they “encountered who had been excluded from the school for medical reasons.” Later, their “enlarged staff of nurses became equally interested in obtaining data regarding” excluded children.

Wald was well positioned to compile and report on the data she gained through observation of her patients. First, she had learned proper methodology as an essential part of her professional nurses’ training. Secondly, she had gained the trust of most of those whom she visited and treated. Finally, from her earliest days on the Lower East Side, she had cooperated with the Board of Health, giving them information that she observed and gathered during her tenement visits. She already routinely reported to the Board on tuberculosis cases, handed out sputum cups, and distributed vaccinations. Soon she was using her growing influence with her neighbors and with members of the Board to share data and stories that illustrated the impact of sick schoolchildren on the general public health.

Wald knew that anecdotal evidence—adding “stories” and real life examples to data—was an extremely effective way to make a case. When one of the Settlement nurses discovered a small boy with scarlet fever attending school and “Tom Sawyer-like, pulling off the skin to startle his little classmates” (the process was called “desquamating,”) she brought the boy “to the President of the Department of Health” and asked him to put on a show. Upon seeing the “exhibit,” Board members revealed that they were already discussing “the possibility of having physicians inspect the school children” in order to cut down on school-spread contagion. They asked Wald to keep producing “evidence of its need” in order to help them in “securing an appropriation for that purpose.”

Settlement nurses complied with the request, collecting and presenting data and parading more “desquamating” children—along with children who had “diphtheria patches on throats” and other diseases—in front of influential members of City government. In October of 1896, under the reform administration of Mayor William Lafayette Strong, the New York City Department of Health moved a step further with its plans, assigning an Inspector to investigate how big a part the “aggregation of children in the schools played in the spread of contagious disease.”

The Inspector visited schools that had reported “cases of contagious disease…to the Department,” went to classrooms “where the sick children had become accustomed to attend,” and examined “all the children present” in these classrooms. The Inspector then visited the homes of all children who were absent from school, “to ascertain the reason for their absence.” From these examinations, the Inspector concluded that “a great number of…absent children were sick with contagious disease,” and that these children had been “directly infected” in “school rooms, where conditions were favorable to infection, viz: heat, stuffiness, overcrowding, and the presence of contagion.” These facts, along with a similar examination of a measles contagion and some anecdotal evidence of how schools contributed to the spread of disease, “were embodied in a special report and forwarded to the Board of Estimate and Apportionment by the Board of Health.”

After receiving the report, the Board of Estimate appropriated a sum “sufficient…to appoint one hundred and fifty sanitary inspectors at the rate of $30 per month, assigned to the daily inspection of schools.” In March of 1897, the City of New York adopted the policy of medical supervision of its schools, “under the control of the Department of Health.”

Although doctors were appointed and sent to the schools, they were not supposed to actually treat the sick children. Their job was limited to examining those who were suspected of harboring contagious diseases, sending “all those who showed suspicious symptoms” out of their classrooms, and notifying “parents of boys or girls in need of medical assistance.”

In March of 1897, the medical inspectors received instructions on their duties. They were each assigned “one or two schools,” and were told “to report to the schools” they had been assigned at “about 9:30 A.M. each school day.” After the doctors arrived, teachers sent them students who were suspected of harboring contagious diseases, and the doctors examined them. In cases of measles or scarlet fever, the “Central Office of the Department of Health” was telephoned immediately and each case “was visited at once by a diagnostician of the Department.” In cases where “the diagnosis was confirmed, instructions were given at the home of the child to ensure…proper isolation” during the course of the illness.

The principal of the school received a “postal…informing him of the presence of contagious disease in the family of the children” who were diagnosed. The “postal” issued a directive to the principal that all children in that family “must be excluded from school attendance until the termination of the case.” Children who had been excluded had to show “a properly signed certificate that the premises had been properly fumigated, and, in the opinion of the officers of the Department of Health, were now free from contagion.”

A “district inspector” was put in charge of each case. This inspector visited each “case” at home “once a week”—more often if there was reason to believe that “proper isolation of the case” was not “observed.” During the first home visit, the district inspector instructed the sick child’s family on “the method of proper isolation,” and pasted “a placard on the door of the apartment.” The placard warned neighbors that a person or persons in that apartment had a contagious illness. Then, the inspector visited each neighbor, informing them of the presence of illness in their building either personally or with a card. When children lived on the premises of businesses, either the business was closed for the duration or the child was removed to the hospital and the business was closed until it had been fumigated. When people disobeyed the instructions of the district inspectors, “a police officer” from the “Health Squad” was assigned to the case,” and threatened forcible removal to the hospital.

Soon the folly of excluding children but not providing a way for treating them became clear. As Josephine Baker revealed,

the results of this first real inspection were tragically astounding. Four out of five of these children, about 80 percent, had pediculosis—the polite medical term for head-lice. One out of five, some 20 percent, had trachoma, that highly infectious eye-disease which constitutes so serious a risk of blindness that the immigration authorities no longer allow any case of it to enter the country.

The “infectious skin diseases—scabies, ringworm and impetigo,” Baker said, “were almost as frequent.”

These “were not school rooms we inspected,” Baker declared, but rather “contagious wards with all the different diseases so mingled that it was a wonder that each child did not have them all.” In fact, “[m]any of them did: lice, trachoma, scabies, ringworm, all at once.” Within the first six months of the program, doctors excluded thousands of children from school for reasons ranging from chicken pox, measles and mumps to diphtheria and trachoma. The “sheer numbers of such cases” meant that the program of medical inspection was “literally depopulating the schools.” In fact, according to an estimate by Baker, “only about 6 per cent.” of the students who were excluded “returned” to school.

The exclusion policy caused other unanticipated problems as well. A “thorough follow-up of actual cases” revealed “[s]erious gaps in the working logic of medical inspection.” First, students

were debarred from class for days, and sometimes for weeks at a time, because families failed to secure additional medical advice to buy prescribed remedies, or to follow orders intelligently. […]

Secondly,

[I]n many cases the excluded children…lost or destroyed the cards. In other instances the cards were taken home, but the parents, often ignorant of the English language, did not understand what the child tried to explain and the Latin names were

incomprehensible to them. “In many instances the cards were never looked at, but remained in their sealed envelopes.” As a result, a majority of the children

received no treatment, especially when the complaints were of an inconspicuous nature and were not considered serious by the parents, such as skin diseases, eye and scalp troubles.

To “cap the climax of this absurd situation,” the very girls and boys who had been sent home—“not fully understanding the instructions”—joined their classmates on the streets and on the playgrounds after school, thus remaining “in close intimacy…with [the very] boys and girls they had been excluded to protect.

As Wald later put it, the system of investigating and excluding “proved to be a perfunctory service and only superficially touched the needs of children.” The “scheme” did, however, serve to make obvious the fact that children needed to be treated as well as diagnosed before the City’s schools could become both universal and safe to attend.

diagnosed before the City’s schools could become both universal and safe to attend.

Tables: Results of school inspection for Manhattan only, September 1897-June 1898 and September 1901 to June 1902.

1A.

| Sept. 1897- June 1898 | Sept. 1901- June 1902 | |

| No. of school days | 196 | 194 |

| No. of schools visited | 294 | 296 |

| No. of visits to schools | 45,754 | 47. 679 |

| Average attendance | 236,677 | 260,182 |

| No. of children examined | 118, 811 | 87,730 |

| No. children excluded | 7,086 | 9,703 |

1 B. Table showing diseases for which children were excluded.

| Sept. 1897- June 1898 | Sept. 1901- June 1902 | |

| Measles | 107 | 85 |

| Diphtheria | 138 | 94 |

| Scarlet fever | 28 | 34 |

| Whooping cough | 135 | 174 |

| Miscellaneous* | 456 | 526 |

| Contagious eye diseases | 3,470 | |

| Pediculosis of head/body | 4,163 | 4,125 |

| Chicken pox | 302 | 354 |

| Skin diseases | 483 | 841 |

*Miscellaneous includes croup, tonsillitis, and mumps.

Bibliography

Baker, S. Josephine, Fighting For Life, NY: The Macmillan Company, 1939.

“Baker, Josephine, Speaker,” in “Nursing News and Announcements,” The American Journal of Nursing, Vol. 10, No. 6 (Mar., 1910), pp. 422-441.

Darlington, Thomas, “Precautions Used by the New York City Department of Health to Prevent the Spread of Contagious Disease in the Schools of the City.” By Thomas Darlington, M.D., Commissions* Of Health Of New York City. From Medical News: A Weekly Journal Of Medical Science. Vol. 86. New York, Saturday, January 21, 1905. No. 3, Pp. 97-104. Find at link

Davis, Allen F., Spearheads for Reform: The Social Settlements and the Progressive Movement, 1890-1914, New York, Oxford University Press, 1967.

[Epstein], Beryl Williams, Lillian Wald: Angel of Henry Street [author’s name on title page is “Beryl Williams”], NY: Julian Messner, Inc., 1948.

Feld, Marjorie N., Lillian Wald: A Biography, Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2009.

Lubove, Roy, The Progressives and the Slums: Tenement House Reform in New York City, 1890-1917, np: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1962.

Rogers, Lina L. “Some Phases of School Nursing” by Lina L. Rogers, R.N. Supervising School Nurse, New York City. American Journal of Nursing, 1908, 8 (12), 966-974. (also reprinted with permission from the American Journal of Nursing in Journal of School Nursing, vol. 18 no. 5, October 2002).

Rogers, Lina, “The Nurse in the Public School,” paper presented at the “Eighth Annual Convention of the Nurses’ Associated Alumnæ of the United States: Minutes of the Proceedings,” The American Journal of Nursing, Vol. 5, No. 11 (Aug., 1905), pp. 725-836. Rogers’ presentation found at pp. 764-773.

Schumacher, Casey, “Lina Rogers: A Pioneer in School Nursing,” The Journal of School Nursing, October 2002, vol. 18 no. 5 247-249.

Wald, Lillian D., The House on Henry Street, N:Y: Henry Holt & Co., 1915.

Wald, Lillian, “Medical Inspection of Public Schools,” Lillian D. Wald, Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 25, City Life and Progress (Mar., 1905), pp. 88-96.

Woods, Robert A. & Albert J. Kennedy, Handbook of Settlements (Russell Sage Foundation), NY: Charities Publication Committee, 1911.

Woods, Robert A. and Albert J. Kennedy, The Settlement Horizon: A National Estimate, New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1922.

Illustrations

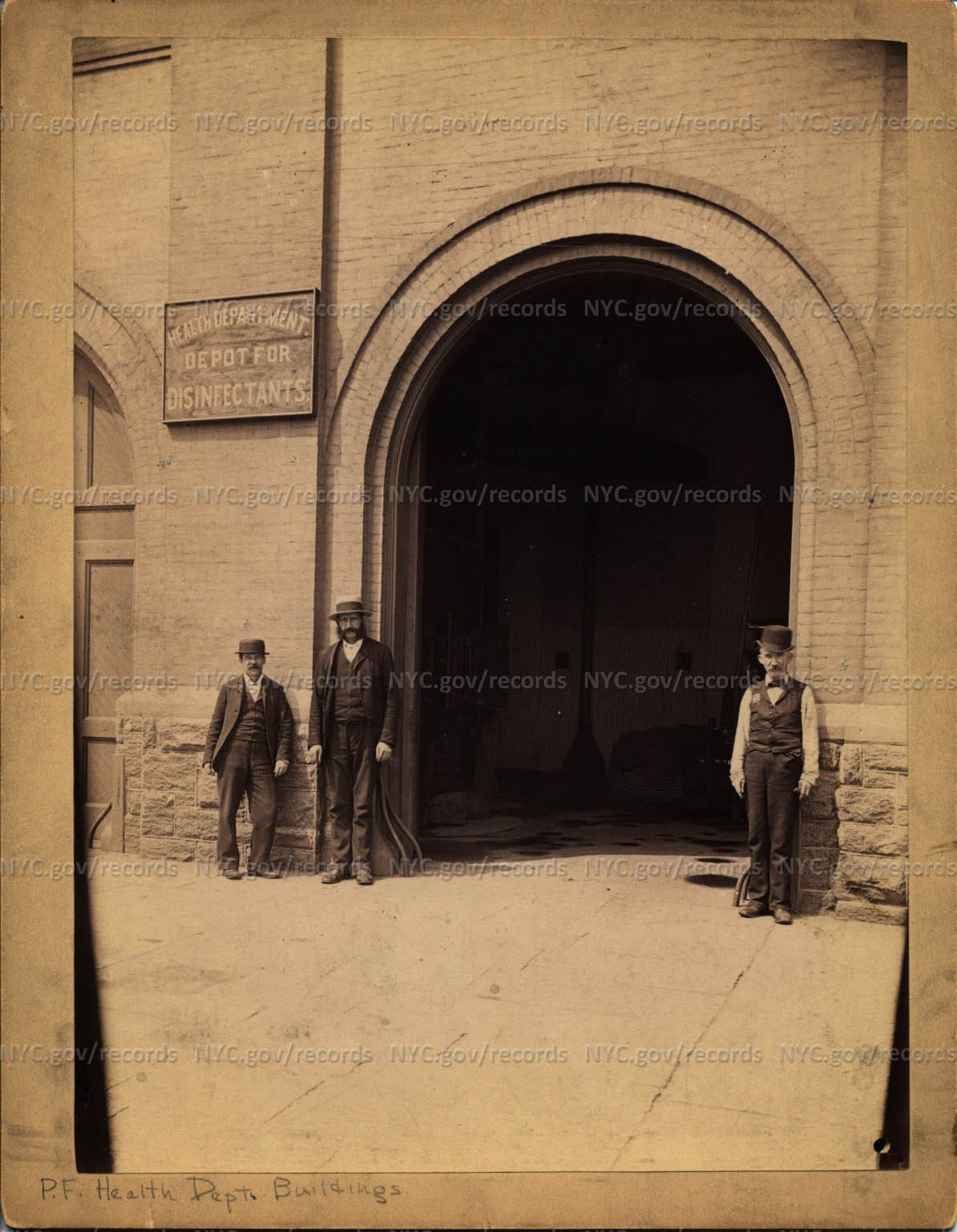

NYC Health Department, Health Department Buildings, Early photograph, 3 men stand in front of Health Department Depot For Disinfectants. 1895-1905. NYC Dept of Records

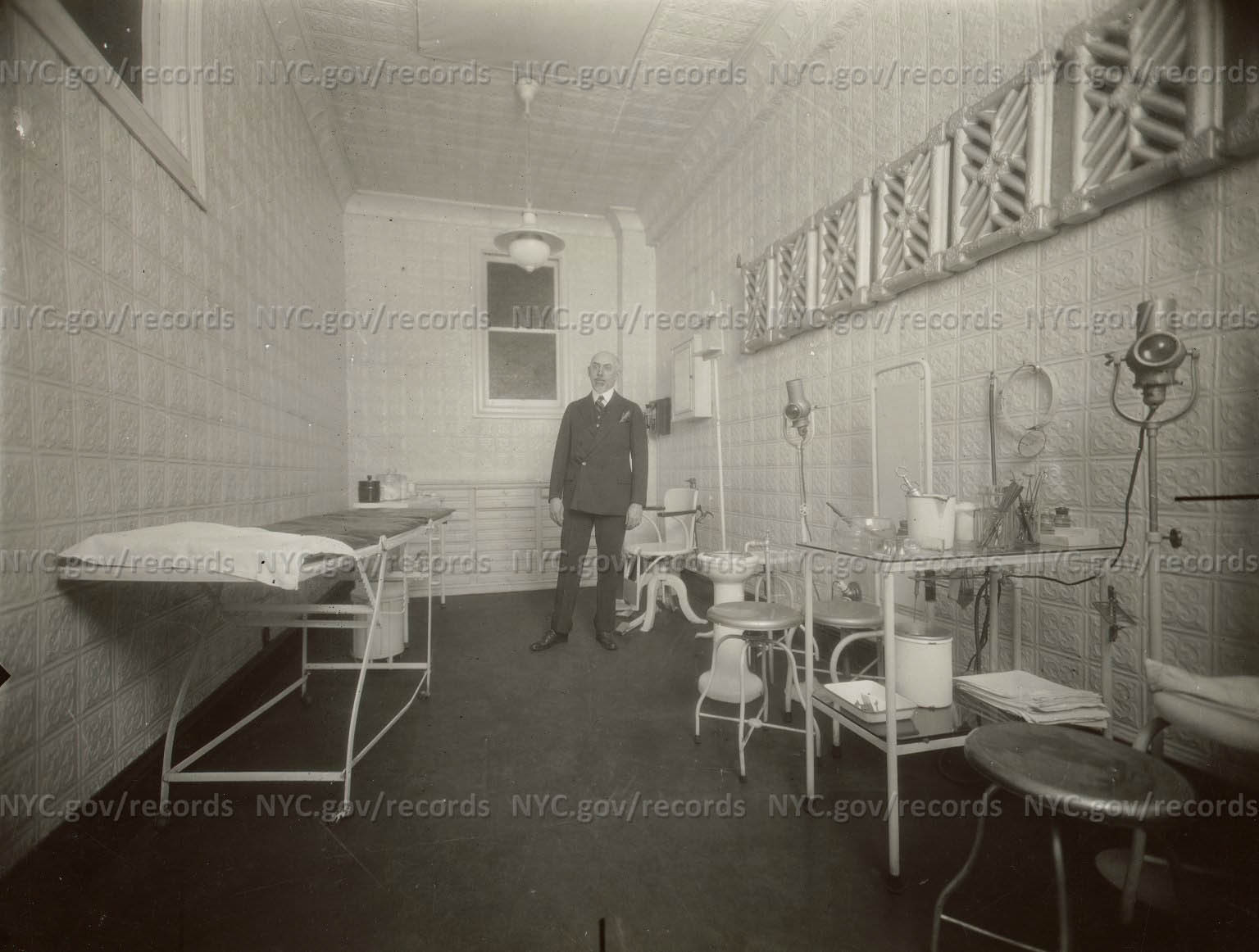

NYC Health Department. Long narrow examination room; Doctor stands in background. Medical paraphernalia. N.d. NYC Dept of Records.

NYC Health Department. Department of Hospitals. Police officer carries unconscious child to awaiting ambulance, 1910-1920. NYC Dept. of Records. http://nycma.lunaimaging.com/luna/servlet/detail/RECORDSPHOTOUNITARC~15~15~1036067~128713:mac_2859?sort=identifier%2Cformat%2Ctype%2Ccurators_choice&qvq=w4s:/what%2FHealth%2BDepartment;sort:identifier%2Cformat%2Ctype%2Ccurators_choice;lc:RECORDSPHOTOUNITARC~15~15&mi=46&trs=48 Current 12/19/16

NYC Health Department. Health Department Buildings. “Depot for Disinfectants.” Four horse-drawn ambulances in front of Disinfecting Building. 1895-1905. NYC Dept. of Records http://nycma.lunaimaging.com/luna/servlet/detail/RECORDSPHOTOUNITARC~15~15~443648~106961:mac_0503?sort=identifier%2Cformat%2Ctype%2Ccurators_choice&qvq=w4s:/when%2F1895-1905;sort:identifier%2Cformat%2Ctype%2Ccurators_choice;lc:RECORDSPHOTOUNITARC~15~15&mi=0&trs=3 Current 12/19/16.

Copyright Anne M. Filiaci 2016Next >