NEW YORK’S PILOT PROGRAM FOR SCHOOL NURSES

Lillian Wald was a reluctant critic of the 1897 reform policy that excluded contagious children from schools. She believed that the Board of Health meant well, but thought that government should take an active role in treating students instead of just sending them home. She also argued that public health nurses could be “an essential factor in…whatever treatment might be suggested for the pupils.” She made this “observation” on a number of occasions to people who could make a difference.

" order_by="sortorder" order_direction="ASC" returns="included" maximum_entity_count="500"]Wald’s critique proved prescient. New York City’s exclusion policy did not provide adequate provision for treatment and follow-up. Soon the schools found themselves literally “depopulated.”

Powerful people were listening to Wald’s ideas—and agreeing with them. At one point, the President of the Board of Health asked Wald “to take part, as nurse, in the medical supervision of the schools.” However, he did not offer to appropriate any money or endow official status for nurses’ services. Wald concluded that it “did not seem wise to accept” the offer, and regretfully declined. She reasoned that the Henry Street Settlement was just beginning to flourish and residents were “embarking upon ventures of their own which would require,” as she put it, “all our facilities and all our strength.” In her mind it “seemed better” for the Settlement to be “free from connections which would make demand upon our energies,” especially if these entailed “routine work” that happened “outside the settlement.”

Wald also reasoned that “the time did not seem ripe for advocating the introduction of both the doctor and the nurse” into the schools. The doctor’s presence alone, she argued, was an “innovation,” and “the appointment of a nurse would have been a radical departure.”

During her trip to England in 1900, Wald found a possible solution to the problem. While attending a tea with her friend Graham Wallas, she met Fabian philanthropist Honner Morten. Morten had recently conducted a limited experiment. Paying out of her own pocket, she had temporarily put a nurse into one of London’s schools. The trial proved successful and officials began to look at the idea of expanding the experiment throughout the school system.

Wald was interested in adapting Morten’s idea in New York City schools. However, nothing came of it until Mayor Seth Low’s reform administration took office on January 1, 1902. Low appointed Dr. Ernst J. Lederly—whom Wald described as “an intelligent friend of children”—to the post of Commissioner of Health. Under Lederly, “the whole department shuddered at the shake-up and housecleaning that occurred.” Lederly made the school system’s “the medical staff” more efficient by reducing their numbers, increasing their salary “to $100 a month,” and demanding “three hours a day…from the doctors.”

The trachoma epidemic in schools first came to light in the spring of 1902, shortly after Lederly took office. Suspecting a problem, he sent a few specialists (“oculists”) into the schools to determine “the prevalence of trachoma among school children.” The specialists found “that about 17 per cent. of the school children examined were afflicted with trachoma to some degree.” This was enough evidence for Lederly to recommend that all school inspectors be “required to take special instruction in the New York Eye and Ear Dispensary” in order to become “better qualified” to diagnose trachoma. Once trained, the regular examiners found so many cases of the disease that “all the dispensaries and hospitals were so congested with trachoma cases that almost no other class of cases could be attended to.”

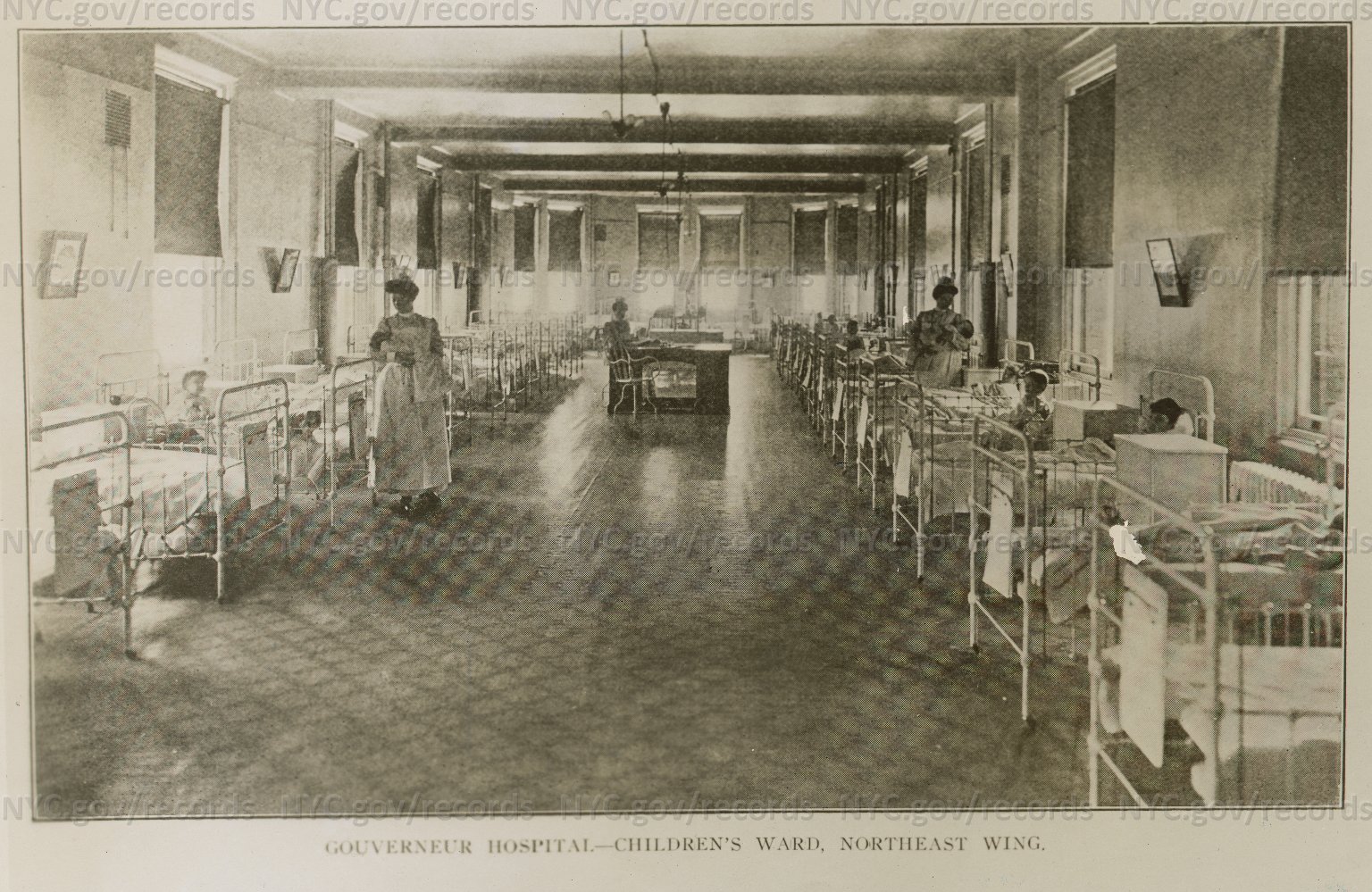

The rise in the number of cases diagnosed led many “authorities of the dispensaries and hospitals” to outright refuse to treat trachoma. They simply did not have the resources. Even when trachoma patients did get the treatment they needed, over-burdened surgeons often failed to complete the accompanying paperwork. Since the Board of Health insisted on “rigid” surveillance and exclusion of infected children, the child who lacked paperwork, even after treated, could not be re-admitted to school. Eventually, authorities were forced to deal with the problem by dedicating the “old portion of the Gouverneur Hospital” as an “Eye Hospital and Dispensary of the Department of Health.”

The aggressive efforts to make schools safe meant that once again “[t]housands of children were sent out of the schools.” This was, as Wald pointed out, not only counterproductive for the individual child’s education. It was also an inadequate response to the epidemic—“[I]n our neighborhood,” she said, “we watched many of them, after school hours, playing with the children for whose protection they had been excluded from the classrooms.” Once again, “[f]ew received treatment…truancy was encouraged, and…classrooms were depleted.”

The Board of Health “bemoaned the fact that the schools” were “depopulated,” but they continued to maintain that “it was their strict duty to exclude” children with contagious diseases in order to protect healthy children. Health Department office employees found themselves “besieged with mothers and children berating inspectors….” It had become “evident” that “this wholesale exclusion of children” was not working.

Thus Seth Low’s reform administration, by being more efficient and demanding, had ironically made the problem more acute. The Boards of Health and Education faced a tricky problem. While one of them was busy “prohibiting children from attending school,” the other was expending efforts “commanding the parents to send them to school.” The Health Commissioner and the President of the Department of Education reached out and “sought guidance in this predicament.” Wald decided that the “time had come when it seemed right to urge the addition of the nurse’s service to that of the doctor” and “suggested to the Board of Education the employment of nurses to see that the advice of school physicians was acted upon.”

School nurses, Wald knew, were the ingredient that would make a medical inspection program work. They could follow up on diagnoses and treat children (or make sure others treated them) for minor contagious illnesses. With nurses in place, Wald reasoned, not only would schools be safer, but fewer “children would lose their valuable school time” in order to make them that way.

Yet Wald was still reluctant to commit the Settlement’s time and resources to an ongoing formal relationship with the school system. Instead, she proposed a variation of Morten’s London plan. In the fall of 1902 she offered and obtained permission to donate the time of one of the settlement’s staff for a demonstration project—but only at a few locations and for a limited amount of time.

Before Wald agreed to the plan, she “exacted a promise from several of the city officials that if the experiment were successful they would use their influence to have the nurse, like the doctor, paid from public funds.” Once she secured this agreement, Wald and other leaders of the pilot project chose four schools “from which there had been the greatest number of exclusions for medical causes.” Lina Rogers, a Settlement resident and “an experienced nurse, who possessed tact and initiative,” agreed to implement a model program in these schools that would last for one month.

Those involved in the project “devised” a routine for the four schools. Every day, the “examining physician” in the chosen schools would send “all the pupils who were found to be in need of attention” to the nurse. With no more than “the equipment of the settlement bag[*] and, in some of the schools, with no more than the ledge of a window or the corner of a room for the nurse’s office,” Lina Rogers “inaugurated” a “system of thorough medical inspection in the schools and of home visiting.”

Rogers incorporated a variety of levels of care for the children. A large proportion of them required

only disinfectant treatment of the eyes, collodion applied to ringworm, or instruction as to cleanliness, and such were returned at once to the class with a minimum loss of precious school time.

With more serious cases, Rogers “called at the home, explained to the mother what the doctor advised, and, where there was a family physician, urged that the child should be taken to him.” When families were too poor to be able to afford a private doctor, Rogers gave them “information as to dispensaries,” and in homes where “there was no one free to take the child to the dispensary, the nurse herself did this.” In cases where children were sent to the nurse simply because they were unclean, “the mother was given tactful instruction and, when necessary, a practical demonstration on the child himself.”

During the course of the month-long trial, Lina Rogers’ completed a total of 893 examinations and treatments, and made 137 visits to the homes of sick school children. While at these homes, she also treated twenty five children who had already been excluded, allowing them to return to school. The month’s trial “proved that, with the exception of the very small proportion of major contagious and infectious diseases,” a nurse’s work “made it possible to reverse” the previous outcome of medical inspection from a program that excluded children to one that kept “the children in the classroom and under treatment.”

At the end of the demonstration project an “enlightened” Board of Estimate and Apportionment voted to allocate the sum of $30,000 to employ trained nurses in the schools. Lillian Wald and Settlement resident Lina Rogers had succeeded in their mission.

*“NURSES’ SETTLEMENT DISTRICT BAG / THE Nurses’ Settlement in New York has … a district nurses’ bag …. modelled after a Boston shopping-bag, with some slight changes. It is wider, and has square box ends. It is twelve inches long, five and a half inches wide, and nine and a half inches high…. There is ….a linen strap for safety-pins…. On the other side of the bag there is one long pocket running from one end to the other for the stationery. On one corner of that is a wide, stiff strap for holding the pencil, spatula, scissors, and two thermometers. The bag can be carbolized inside and out. The contents are as follows:

One three-ounce bottle for alcohol; five one-ounce bottles containing respectively listerine, whiskey, glycerine, tincture of green soap, and carbolic acid, ninety-five per cent.; one wide-mouthed bottle with screw-top for bichloride tablets; one one-ounce wide-mouthed bottle with screw-top for boracic acid powder; small screw-top bottle for cascara tablets; one two-ounce porcelain jar containing boracic acid unguent; two one-ounce porcelain jars with ichthyol unguent, ten per cent., and Thiersch powder; one one-ounce porcelain jar for special dressing containing iodoform, balsam Peru, etc.; half-ounce porcelain jar for vaseline; one white-enamel bowl, used as soap-dish and measure, holding six ounces; one cake of soap; nail-brush; hand-towel; apron of light-weight muslin, made like a butcher’s apron; white-enamel funnel; spatula; pencil with tip; two thermometers rectal, mouth; scissors; instrument case of linen, containing rubber and glass catheters, a syringe and a dropper of glass, forceps, probe, and wooden picks; toilet powder in shaker; safety-pins, large and small; linen bag for gauze and unbleached bandages; linen bag for dressings, containing gauze rolls, absorbent and non-absorbent cotton, linen, and pads; stationery, consisting of bedside notes, brown envelopes in which to keep them, and pad; rubber tissue; adhesive plaster….. The instrument case…. has one pocket for holding the rubber catheter, which measures five and a half inches long by three and a quarter deep….The bag, exclusive of the fittings, costs three dollars and fifty cents. M. M. B.” Excerpt from “Editor’s Miscellany,” The American Journal of Nursing, Vol. 1, No. 10 (Jul., 1901), pp. 766-773, “Nurses Settlement District Bag”, pp. 769-772, includes photos of bag and contents).

Bibliography

Baker, S. Josephine, Fighting For Life, NY: The Macmillan Company, 1939.

Baker, Josephine, Speaker, “Nursing News and Announcements,” The American Journal of Nursing, Vol. 10, No. 6 (Mar., 1910), pp. 422-441.

Bullough, Vern L., and Bonnie Bullough, The Emergence of Modern Nursing, 2d ed., London: The Macmillan Co., 1969.

Bullough, Vern and Bonnie, The Care of the Sick: the Emergence of Modern Nursing, NY: Prodist, 1978.

Daniels, Doris Groshen, Always a Sister: The Feminism of Lillian D. Wald, New York, Feminist Press, 1989.

Darlington, Thomas, “Precautions Used by the New York City Department of Health to Prevent the Spread of Contagious Disease in the Schools of the City.” By Thomas Darlington, M.D., Commissions* Of Health Of New York City. From Medical News: A Weekly Journal Of Medical Science. Vol. 86. New York, Saturday, January 21, 1905. No. 3, Pp. 97-104.

Davis, Allen F., Spearheads for Reform: The Social Settlements and the Progressive Movement, 1890-1914, New York, Oxford University Press, 1967.

Dock, Lavinia, “School Board Nurses,” and “Lederle,” excerpts in “Foreign Department,” The American Journal of Nursing, Vol. 3, No. 5 (Feb., 1903), pp. 396-401.

Dock, Lavinia, “School-Nurse Experiment in New York,” by L. L. Dock, The American Journal of Nursing, Vol. 3, No. 2 (Nov., 1902), pp. 108-110.

Dolan, Josephine A., Goodnow’s History of Nursing, Eleventh Edition, Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Co., 1963.

Duffus, R.L., Lillian Wald: Neighbor and Crusader, New York: The Macmillan Company, 1939.

[Epstein], Beryl Williams, Lillian Wald: Angel of Henry Street [author’s name on title page is “Beryl Williams”], NY: Julian Messner, Inc., 1948.

Henry Street Settlement, “Our History,” (1902) http://www.henrystreet.org/about/our-history/ Current 1/2/17.

Hunting, Harold B., “Lillian Wald: Crusading Nurse,” in Lotz, Philip Henry, ed., Distinguished American Jews, (Creative Personalities, v. VI), NY: Association Press, 1945.

Morten, Honnor, “The London Public-School Nurse,” Honnor Morten. The American Journal of Nursing Vol. 1, No. 4 (Jan., 1901), pp. 274-276.

Mottus, Jane E., New York Nightingales: The Emergence of the Nursing Profession at Bellevue and New York Hospital 1850-1920, [Revision of thesis-Ph.D.), New York University, 1980], Ann Arbor, MI, UMI Research Press, c1981, 1980.

Notable American Women 1607-1950: A Biographical Dictionary, Edward T. James, Janet Wilson James, & Paul S. Boyer, eds., v.3, Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1971.

“Nurses Settlement District Bag,” in “Editor’s Miscellany,” The American Journal of Nursing, Vol. 1, No. 10 (Jul., 1901), pp. 766-773, “Nurses Settlement District Bag”, pp. 769-772, includes photos of bag and contents).

“Official Reports,” The American Journal of Nursing, Vol. 9, No. 1 (Oct., 1908), pp. 56-64 (“A RESIGNATION which will cause regret is that of Lina L. Rogers from the staff of school nurses of New York City….)

“Professional Nursing in School and Tenement,” New York Times, August 27, 1905.

Rogers, Lina, “The Nurse in the Public School,” paper presented at the “Eighth Annual Convention of the Nurses’ Associated Alumnæ of the United States: Minutes of the Proceedings,” The American Journal of Nursing, Vol. 5, No. 11 (Aug., 1905), pp. 725-836.

Rogers, Lina, Reporting in “Official Reports of Societies,” in The American Journal of Nursing, Vol. 3, No. 7 (Apr., 1903), pp. 556-571, p. 566.

Rogers, Lina L. “Some Phases of School Nursing” By Lina L. Rogers, R.N. Supervising School Nurse, New York City, American Journal of Nursing, 8 (12), 966-974, 1908. Reprinted with permission in the October 2002 issue of the Journal of School Nursing.

Rogers, Lina, “A Year’s Work for the Children in New York Schools,” Lina L. Rogers. The American Journal of Nursing, Vol. 4, No. 3 (Dec., 1903), pp. 181-184.

Schumacher, Casey, “Lina Rogers: A Pioneer in School Nursing, The Journal of School Nursing, October 2002 vol. 18 no. 5 247-249.

Smith, Helena Huntington, “Profiles: Rampant but Respectable; Lillain D. Wald,” The New Yorker, Dec. 14, 1929.

Wald, Lillian D., The House on Henry Street, N:Y: Henry Holt & Co., 1915.

Wald, Lillian, “Medical Inspection of Public Schools,” Lillian D. Wald, Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 25, City Life and Progress (Mar., 1905), pp. 88-96.

Wald, Lillian D., Lillian Wald Papers. New York: New York Public Library, 1983.

Woods, Robert A. & Albert J. Kennedy, Handbook of Settlements (Russell Sage Foundation), NY: Charities Publication Committee, 1911.

Woods, Robert A. and Albert J. Kennedy, The Settlement Horizon: A National Estimate, New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1922.

Illustrations

Gouverneur Hospital Children’s Ward. 3 children seated at low table; others are in beds. May, 1902. NYC Dept. of Records. Link to Illustration

Gouverneur Hospital Children’s Ward, northeast wing. May, 1902 NYC Dept. of Records. Link to Illustration Current 1/11/17

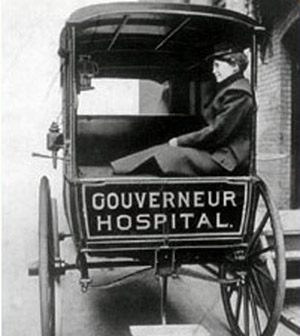

Gouverner Hospital Dr. Emily Dunning Barringer as a resident at Gouverneur, c. 1900.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gouverneur_Health#/media/File:EmilyDunningBarringer.jpg Current 1/11/17

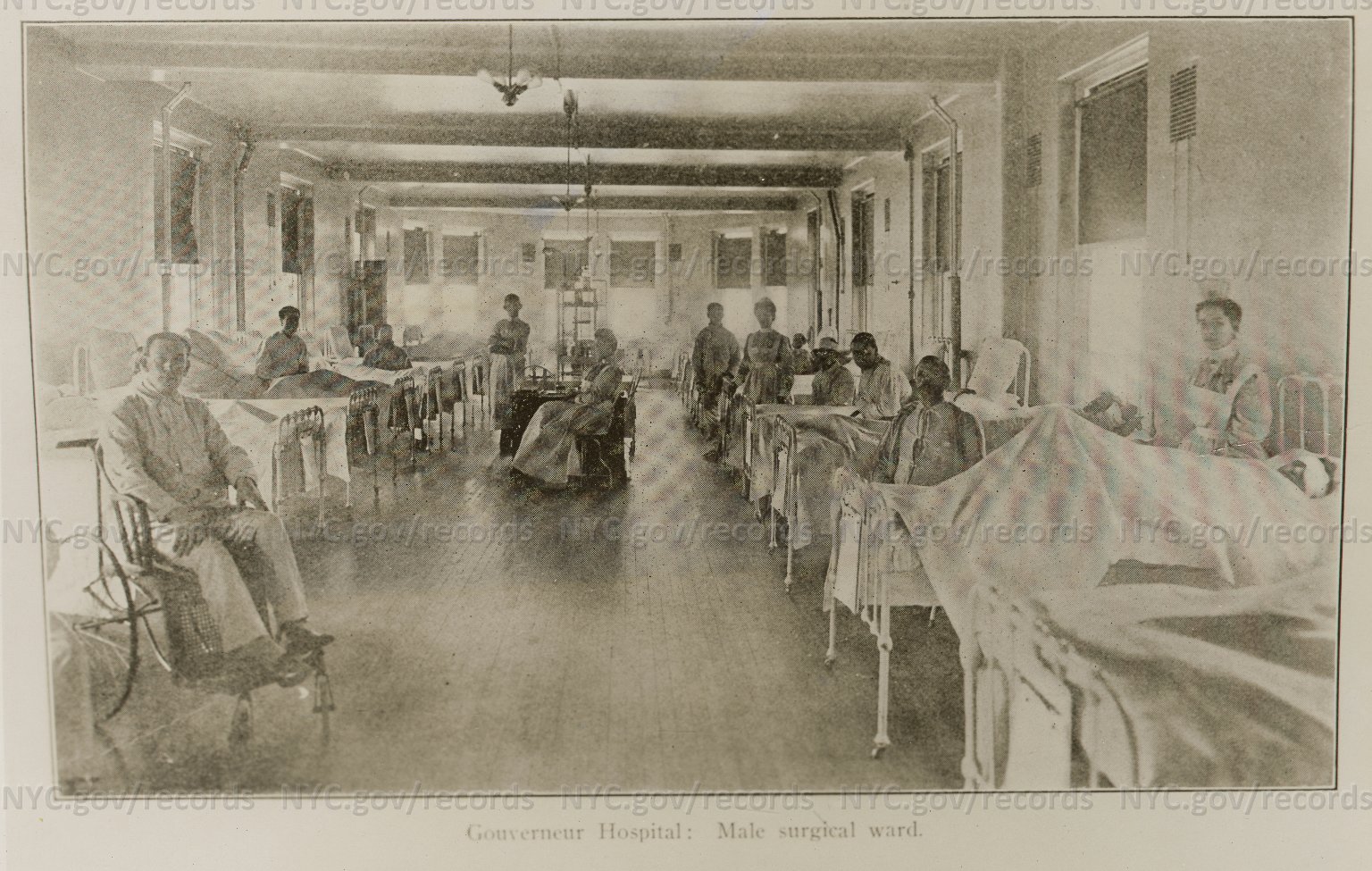

Gouverner Hospital Male Surgical Ward. Patients, mostly sitting up, and several nurses. May, 1902. NYC Dept. of Records. Link to Illustration Current 1/11/17

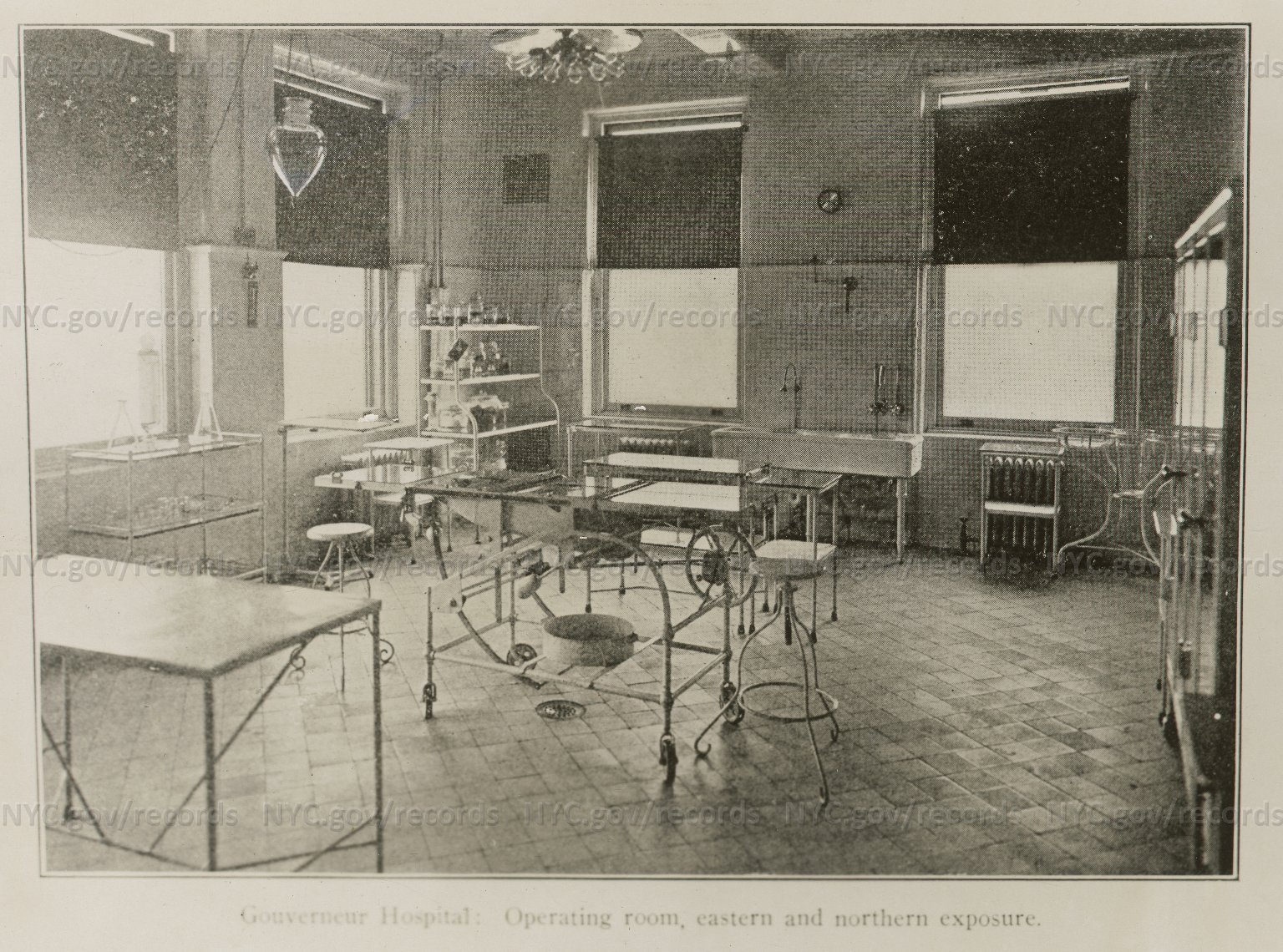

Gouverner Hospital Operating Room, eastern and western exposure. May 1902. NYC Dept. of Records. Link to Illustration Current 1/11/17

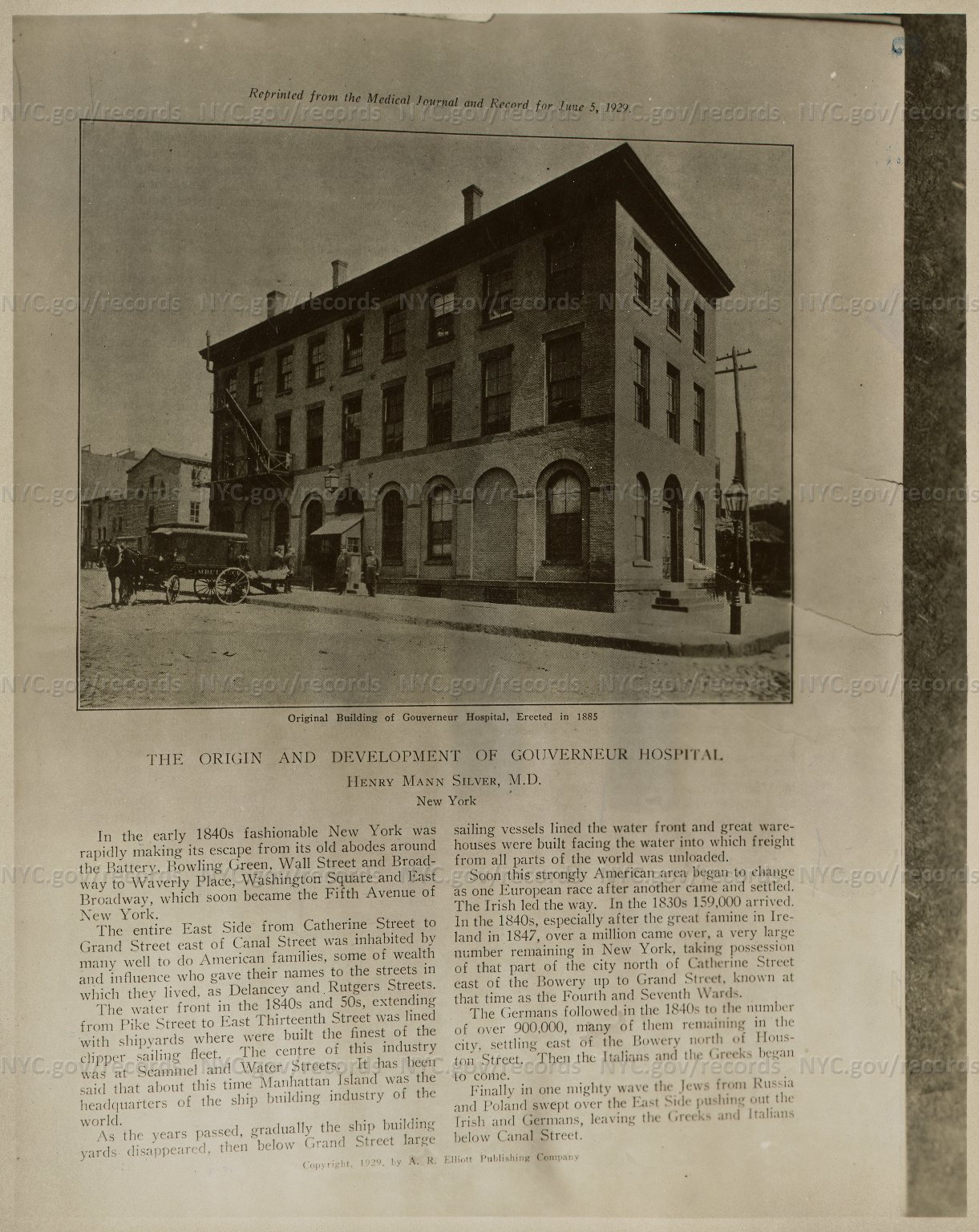

Gouverner Hospital, Original building of Gouverneur Hospital (formerly a market) on Gouverneur Slip, erected in 1883. Horse-drawn ambulance. NYC Department of Records. Page from Medical Journal & Record 6/5/1929 Link to Illustration Current 1/11/17

Gouverneur Hospital: Patients on curved verandas with protective shades. Ambulance garage center; dispensary at R. 1913-1917. NYC Dept of Records. Link to Illustration Current 1/11/17

Gouverneur Hospital. Southeast elevation. Showing wings for wards. Ambulance house and stable between wings. 1907-1910. NYC Dept. of Records. Link to Illustration Current 1/11/17

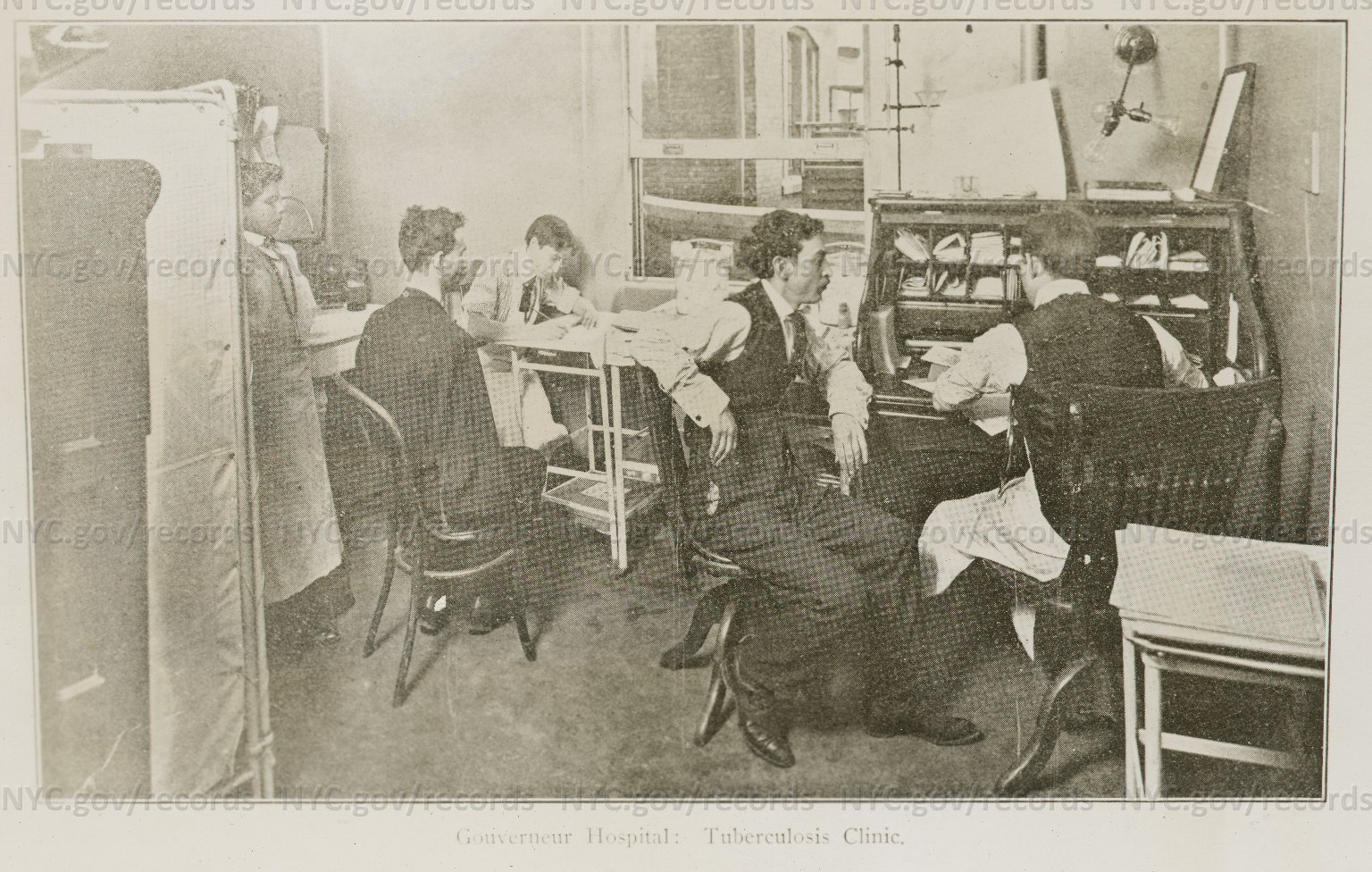

Gouverneur Hospital Tuberculosis Clinic. Seated patient with man at desk taking notes. Another patient background. May, 1902. NYC Dept. of Records. Link to Illustration Current 1/11/17

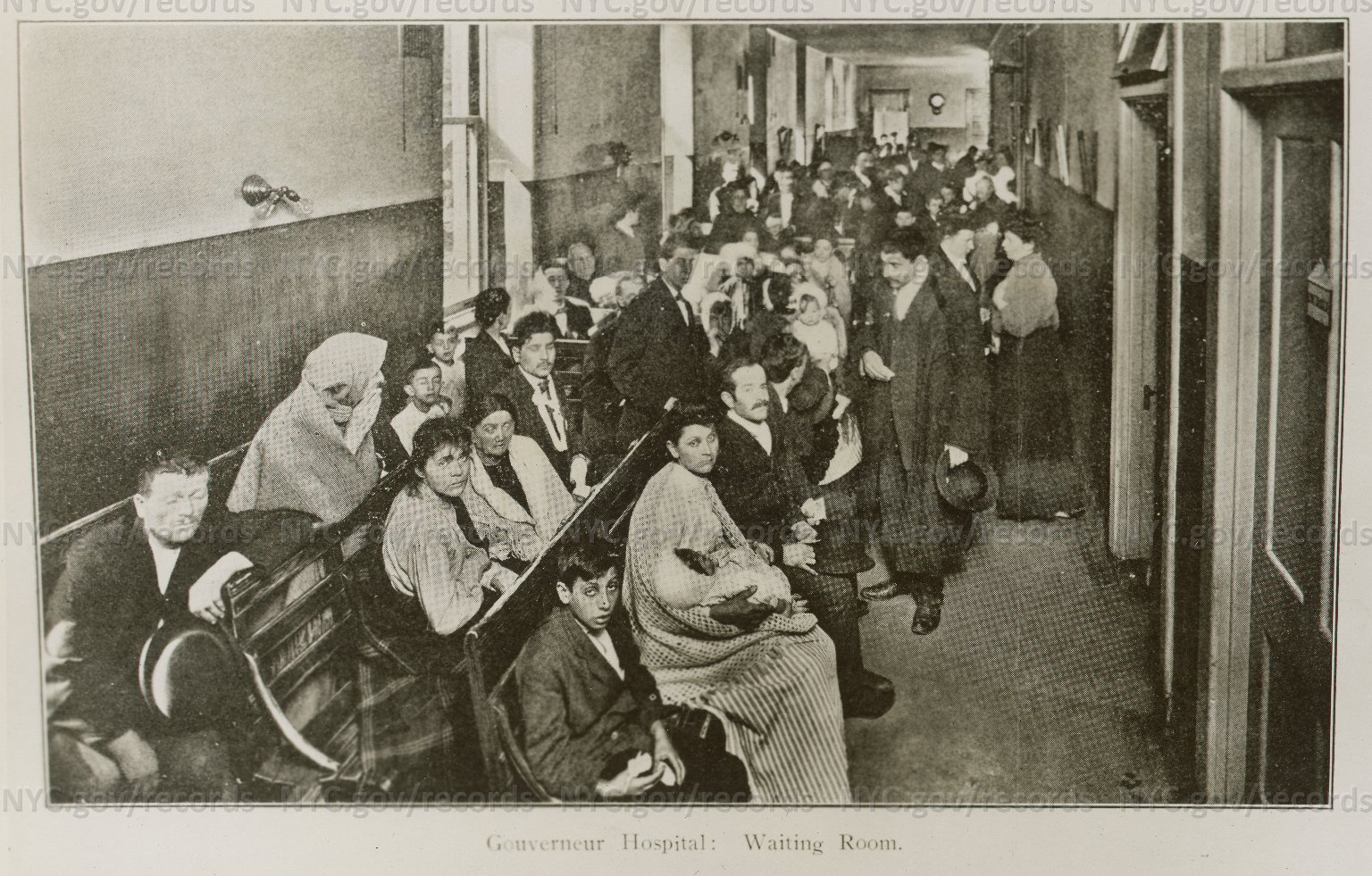

Gouverneur Hospital Waiting Room: Patients crowded on benches, some standing, in hallway. May, 1902. NYC Dept. of Records Link to Illustration Current 1/11/17

Low, Seth, Seth Low, head-and-shoulders portrait. Public Domain. Created 31 December 1900. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seth_Low#/media/File:Seth_Low_cph.3a37073.jpg Current 1/11/17

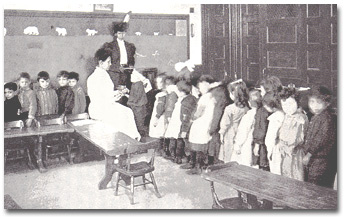

Rogers, Lina, with schoolchildren. Caption reads: The superintendent of nurses, Ms. Lina Rogers, inspecting school children. http://www.harvardsquarelibrary.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/jb2-baker6a.jpg Current 1/6/17

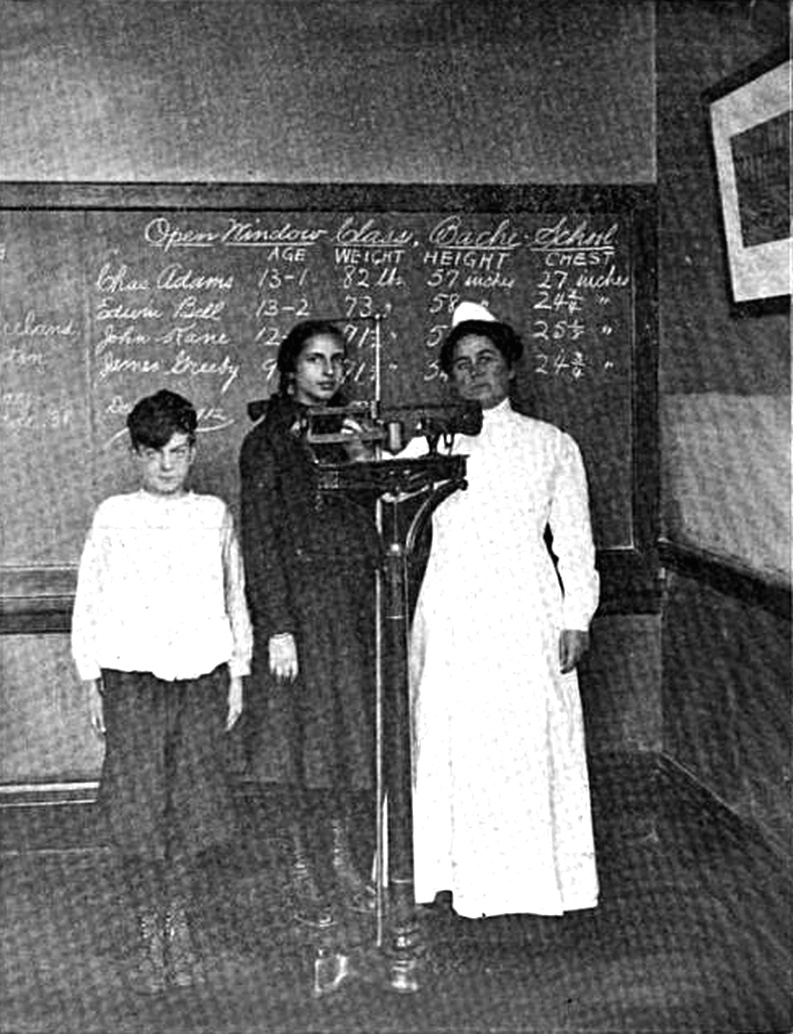

School nurse weighing and measuring pupils, Philadelphia PA ca. 1912 This IMAGE (or other media file) is in the public domain because its copyright has expired. This applies to the United States, where Works published prior to 1978 were copyright protected for a maximum of 75 years. Works published before 1923 (in this case c 1913) are now in the public domain. Title: American journal of public health: the journal of the American Public Health Association, Volume 3, Issues 1-6. Author: American Public Health Association. Publisher: American Public Health Association, 1913. Original from: the University of California. Digitized: Aug 3, 2007. Subjects: Medical › Public Health Medical / Public Health, Public health

TEXT CREDIT: American journal of public health: the journal of the American Public Health Association, Volume 3, Issues 1-6 http://publicdomainclip-art.blogspot.com/2011/09/school-nurse-weighing-and-measuring.html Current 1/6/17

Wallas, Graham. Younger years. Public domain. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Graham_Wallas#/media/File:Graham_Wallas.jpg Current 1/11/17

Wallas, Graham, Graham Wallas portrait taken c.1920s. Public domain. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Graham_Wallas#/media/File:Graham_Wallas,_c1920s.jpg Current 1/11/17

Copyright Anne M. Filiaci 2016