Tracking Illness–The Index Card System

By 1903, the “number of exclusions” in New York City’s schools had been “reduced” by allowing children with contagious diseases to stay in school as long as they were being treated. However, the system could only work if the affected children “could be followed and watched closely” to make sure that the medical inspectors’ instructions “were observed.” The City had charged school nurses with this task, but nurses could only do the follow-up and treatment necessary if they had adequate and up-to-date information on each sick child. Managing contagious illness required keeping records that tracked its course. In order to ensure better record-keeping, on March 23, 1904 the Board of Health introduced a “card system” (or a “card index system”).

" order_by="sortorder" order_direction="ASC" returns="included" maximum_entity_count="500"]As a part of this system, the Board gave code numbers to diseases. This was meant to maintain privacy and to avoid embarrassment for the infected child. Under the new system, each class had a card. When the medical inspector examined a child who had a communicable disease, “the code number of the disease” was “called out to the teacher, who, seated at her desk” wrote “the child’s name and code number of the disease on the class card.”

If the school had a nurse on staff, “all cases, with the exception of trachoma, measles, etc.,” were sent to her for treatment. She, in turn, learned the diagnosis “from the class card or from a special piece of paper,” and treated the child “according to the rules adopted by the Department of Health.”

Course of Treatment Outlined by the Department of Health

Pediculosis. – Saturate head and hair with equal parts kerosene and sweet oil, next day wash with solution of potassium carbonate (one teaspoonful to one quart of water) followed by soap and water. To remove “nits” use hot vinegar.

Favus,,Ringworm of Scalp. –Mild cases: scrub with tincture green soap, epilate, cover with flexible collodion. Severe cases: Scrub with tincture green soap, epilate, paint with tincture iodine and cover with flexible collodion.

Ringworm of Face and Body.– Wash with tincture green soap and cover with flexible collodion.

Scabies. – Scrub with tincture green soap, apply sulphur ointment.

Impetigo. – Remove crusts with tincture green soap, apply white precipitate ointment (ammon. hydrarg.).

Molluscum Contagiosum. – Express contents, apply tincture iodine on cotton toothpick probe.

Conjunctivitis. – Irrigate with solution of boric acid.

The nurses prided themselves on caring for each case separately. Even if a number of children had the same ailment and needed instructions for treatment, the nurse “treated and advised” all cases “individually,” because they “found that direction given to large numbers of children at a time” did “not accomplish so well the desired end.”

If the nurse saw that the medical inspector had written “a number on a card” that indicated the child was contagious, the child was “excluded from school for the time necessary to effect a cure, and a nurse attends him, free of charge, at his home.” The child was “given a properly filled” out “exclusion card giving the name, age, residence of the child,” as well as “the number and location of the school.” The “exclusion card” was “given to the principal, who” in turn gave it “to the child in a sealed envelope furnished by the Department of Health.” These cards constituted parental notices, and schools sent them home in sealed envelopes in an additional attempt to maintain patient privacy.

The sealed envelopes were necessary because before, “it was not uncommon to learn that a little ‘tot’ excluded from school for pediculosis would run along the streets exultantly showing this card to all her friends thinking it a good ticket from the school. Imagine,” Dr. Darlington added, “the chagrin of the parents when they read this card excluding their child from school for pediculosis capitis.”

Children with head lice (pediculosis) or other minor contagious diseases could remain in school as long as they could prove that they were being treated. The index system’s “class card” contained “the date on which the child was ordered under treatment.” On “a subsequent visit to the class, the inspector” would call out “the names of all the children ordered under treatment on a previous visit.” If a child showed “no evidence of having had treatment,” he or she was “excluded forthwith” and was “not allowed to return to school until readmitted by the school inspector.” The child was only allowed back once “evidence” of “bona fide treatment” was “established.” Medical examiners inspected classes “as far as possible,” every week. Inspectors noted how many children remained under treatment, which diseases were being treated, and whether there were new cases. With the system in place, it was “possible to find out, within 24 hours, just how many cases” were “under treatment in all schools….”

With the card system, children would not only be assured of treatment; they would also be assured of returning to school once they were healthy. The date that children were supposed to return to school was “marked on the back of the exclusion card,” allowing health professionals to make sure that excluded children returned to school once they were no longer contagious.

Once an efficient system had been established to track the progress of excluded children, officials soon found that the continued “truancy” of some was not only because treatment was inadvertently overlooked. It soon became clear that a “number of parents were pleased that their children were excluded from school” because it meant that they could be used at home—as babysitters and as sweatshop labor. The longer these parents could “neglect getting children under treatment,” the longer they would have an extra pair of hands to work at home.

To combat this practice, the City Superintendent of Schools, District Superintendents, and the District Attorney’s office declared that parents who refused to put their children “under proper medical treatment” so that they “may return to school” were “violating the compulsory educational law” and were “guilty of a misdemeanor punishable by a fine.” The City won a test case on this issue, with the court fining the parent of an untreated child ten dollars. The enforcement of fines meant that it would no longer be profitable for parents to keep their children out of school.

The card system proved to be an effective complement to medical inspection and nursing care. Health professionals could now track the progress of sick children and make sure that they returned to school when they had been cured. The adoption of the numerical code system, however, proved less than effective as a way to maintain patient privacy.

Health professionals had “hoped” that “by simply stating the number” that “the ailment” was given under the code, “nurses and physicians would know the nature and the malady and the other children would be kept in ignorance.” But the children had other ways of determining just who was sick and with what. One nurse, leaving her “school just after the children had issued from the door for recess” was “appalled to hear the children taunting those who had diseases by calling them the names of their afflictions.” Two poor little girls with “hooded heads and short cropped hair” were taunted by calls of “Pediculosis! Pediculosis,” while another student, “whose hand was bound in a bandage,” was hounded by cries of “Ringworm! Ringworm!”

Children were quick to use the numbering system to torment their classmates as well. “When the system was first adopted,” Darlington revealed, “No. 6 meant pediculosis. It was only one week after it had started when every child in the school knew No. 6 meant ‘pediculosis.’” To counter this, the common yet embarrassing disease of pediculosis was giving four different numbers—two, four, six and eight. Health officials had “hoped by this means to confuse the children.” Yet soon, to nurse’s “consternation,” she “heard children shouting “Two-four-six-and-eight!’ at a hooded figure, who did not relish the name at all.” Darlington, figuratively throwing up his hands, stated that he believed “the system should have been changed each week” if they were to have any hope of “fool[ing] the young American in public schools of the city.”

Achieving and maintaining healthy schools in New York City meant pursuing a program of trial and error. The system was imperfect at its start, and each new innovation revealed another set of problems. Yet by pursuing solutions over a number of years with open minds, patience, and flexibility, reformers came ever closer to succeeding in their goal of creating public schools that were not only healthy, but accessible to all of the City’s children.

Bibliography

Darlington, Thomas, “Precautions Used by the New York City Department of Health to Prevent the Spread of Contagious Disease in the Schools of the City,” by Thomas Darlington, M.D., Commissioner of Health of New York City. From Medical News: A Weekly Journal of Medical Science, vol. 86, No. 3, pp. 97-104. New York, Saturday, Jan. 21, 1905. Original articles from Google Books at https://books.google.com/books?id=NS4TAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA97&dq=darlington+precautions+new+york+city+department+of+health+schools+1905&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiGoYnV-_jQAhUBSSYKHQAyDhgQ6AEILTAB#v=onepage&q=darlington%20precautions%20new%20york%20city%20department%20of%20health%20schools%201905&f=false Current 1/26/17

“Professional Nursing in School and Tenement,” New York Times, August 27, 1905.

Rogers, Lina L. “Some Phases of School Nursing” by Lina L. Rogers, R.N. Supervising School Nurse, New York City. American Journal of Nursing, 1908, 8 (12), 966-974. (also re-printed with permission from the American Journal of Nursing, in Journal of School Nursing, October 2002).

Illustrations

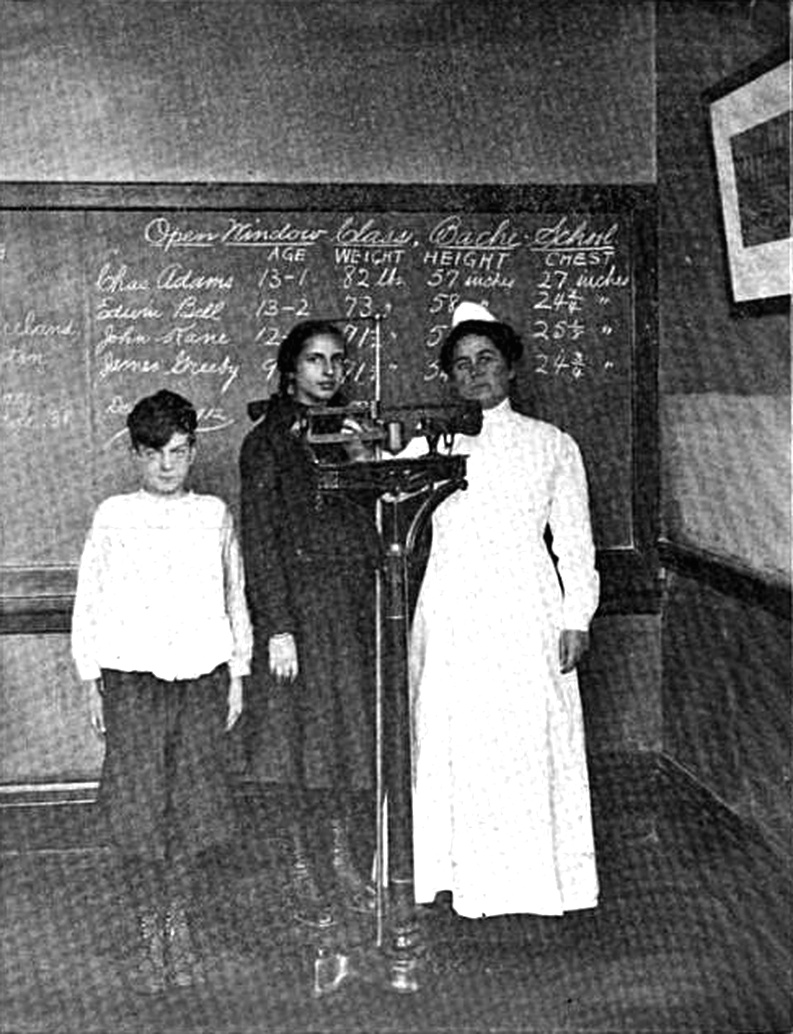

School nurse weighing and measuring pupils, Philadelphia PA ca. 1912 This IMAGE (or other media file) is in the public domain because its copyright has expired. This applies to the United States, where Works published prior to 1978 were copyright protected for a maximum of 75 years. Works published before 1923 (in this case c 1913) are now in the public domain. Title: American journal of public health: the journal of the American Public Health Association, Volume 3, Issues 1-6. Author: American Public Health Association. Publisher: American Public Health Association, 1913. Original from: the University of California. Digitized: Aug 3, 2007. Subjects: Medical › Public Health Medical / Public Health, Public health

TEXT CREDIT: American journal of public health: the journal of the American Public Health Association, Volume 3, Issues 1-6 http://publicdomainclip-art.blogspot.com/2011/09/school-nurse-weighing-and-measuring.html Current 1/20/17

Hanink, Elizabeth, “Lina Rogers, the First School Nurse,” Working Nurse nd. Link to article with image http://www.workingnurse.com/articles/lina-rogers-the-first-school-nurse Current 1/24/17 Link to image only http://www.workingnurse.com/images/articles/big/webschool_nurse3_small.jpg Current 1/24/17

Copyright Anne M. Filiaci 2016

< PreviousNext >