NURSES REDUCE INFANT MORTALITY RATE—NEW YORK CREATES DIVISION OF CHILD HYGIENE

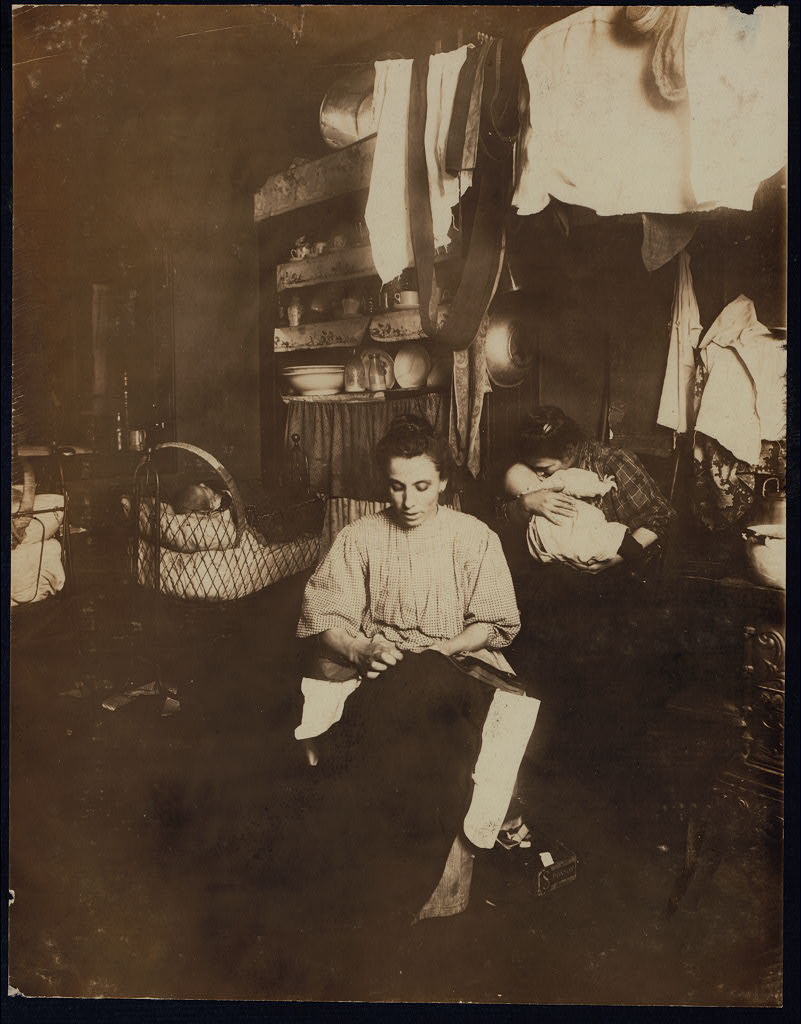

Unlike teachers, school nurses worked year round. According to a 1905 New York Times article, they spent their summers visiting tenements, “curing disease where it is found, and preventing it wherever it is possible for them to prevent it.” Their preventive work included teaching new mothers the benefits of breastfeeding (“nursing sick babies”), as well as providing basic advice on “household hygiene,” and giving “lessons in preparing food.”

" order_by="sortorder" order_direction="ASC" returns="included" maximum_entity_count="500"]The school nurse’s summer work resembled the daily activity of the Henry Street visiting nurse, with the exception that it targeted infants and children and was funded by the taxpayer. Within the space of a few years, these efforts proved promising enough for city officials to take notice. In 1908, Dr. Walter Bensel, the Department of Health’s Sanitary Superintendent, and Dr. Thomas Darlington, Commissioner of Public Health, decided to formalize and expand the school nurses’ summer public health outreach. Acting on a Bureau of Municipal Research recommendation, they determined to create a separate entity dealing specifically with children’s health.

Before they sought formal recognition and funding for this new division, Bensel and Darlington decided to implement a limited pilot program and study its results. In the early summer of 1908, Dr. Bensel called Dr. Josephine Baker, a graduate of the Woman’s Medical College, “into his office…to tell me I might have a try at it.” Baker emerged from Bensel’s office on that summer day “the proud and bewildered Chief of the newly-created Division of Child Hygiene.”

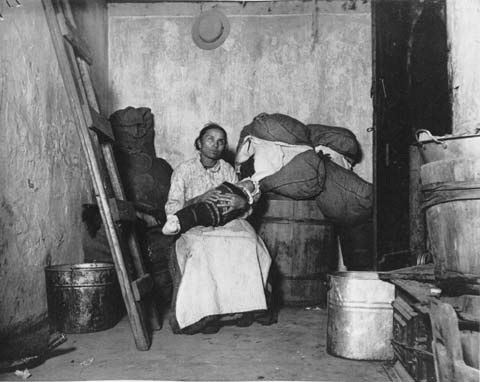

The title was just about the only tool Baker possessed—the job came with “no staff” and “no money.” But Baker did have “an idea” about how she would like to proceed. During the City’s summer months, a stunning total of about 1,500 babies died each week of dehydration resulting from diarrhea. Baker decided that she would target this particular problem. Her plan was to use school nurses “in an experiment in preventive child hygiene” during these summer months—when the nurses were “at liberty” from their daily school duties and were already occupied visiting tenements.

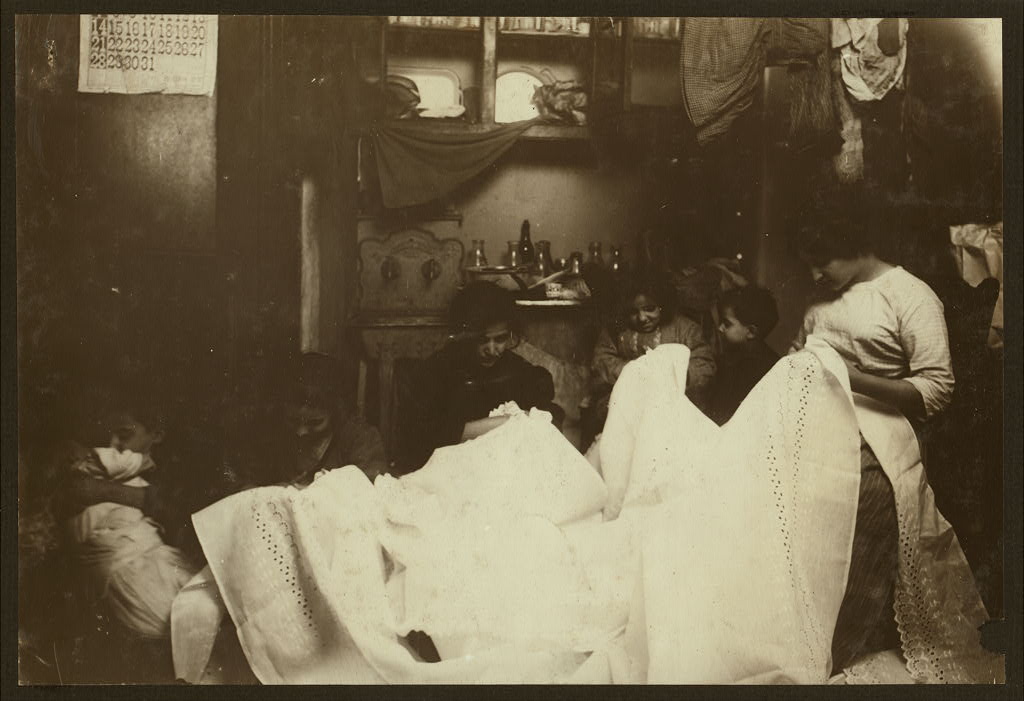

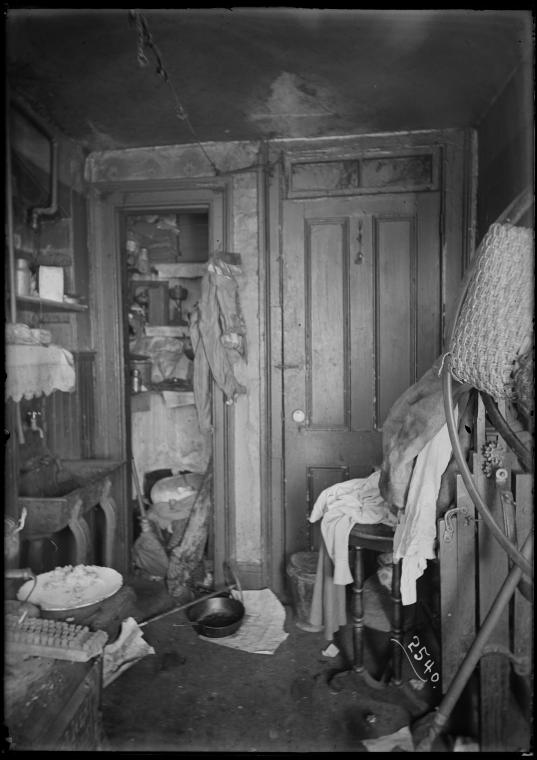

During “several consultations” with Darlington and Bensel, Baker outlined her proposed project, and suggested limiting its scope by placing the nurses “in a district” that normally had “a very high baby death rate.” The two health officials gave their consent for “a trial experiment, and Baker “selected” a site that consisted of “a complicated, filthy, sunless and stifling nest of tenements on the lower east side of the city.”

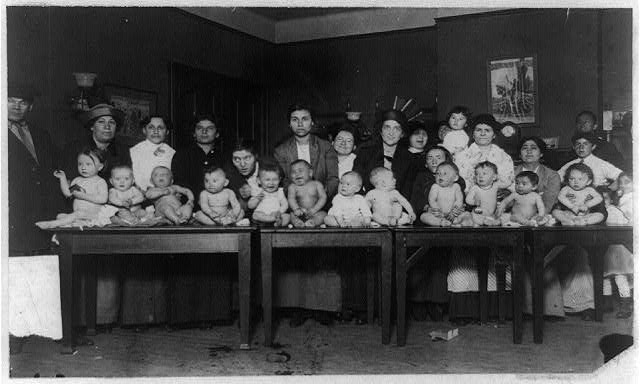

Each day during the course of the project, the Health Department’s Registrar of Records sent Baker “the name and address on the birth certificate of every baby whose birth had been reported on the previous day.” “Within a few hours,” Baker had dispatched a “graduate nurse, thoroughly instructed in the way to keep a well baby well,” to the addresses she had received. The nurse acquainted herself with mother and baby, and proceeded to “go into the last fine detail of just how that baby should be cared for.” The instructions were “[n]othing revolutionary, just insistence on breast-feeding, efficient ventilation, frequent bathing, the right kind of thin summer clothes, out-of-door airing in the little strip of park around the corner.” If the mother of a newborn proved to be “sulky, or apprehensive,” the nurse would visit “again and again, wearing down their resistance” and “establishing friendly contact, until they were ready and willing to cooperate.”

Dr. Josephine Baker expected this experiment to be somewhat successful but she “was not prepared…for the impressiveness of the facts when the results of the summer’s campaign in that corner of the east side were tabulated.” While “everywhere else in town the summer death rate of babies had been quite as bad as ever,” in Baker’s experimental district “there were 1200 fewer deaths than there had been the previous summer.”

Once the facts were in, the City acted quickly. On August 8, 1908, the municipal government officially approved creation of the Division of Child Hygiene of the New York City Department of Health, with Dr. Josephine Baker as its Chief. The Board of Estimate and Apportionment ensured the division’s viability by allocating money in “fairly generous amounts.” The City expanded school health programs as well, and transferred them to the jurisdiction of the new entity.

Shortly after the Division of Child Hygiene was created, Lina L. Rogers tendered her resignation as Supervising Nurse of New York City’s schools. Her actual resignation, which took effect on October 1, 1908, signaled the beginning of a new era. The school nurse—a radical innovation less than a decade earlier—now had an expanded mission formally ensconced within the City’s Department of Health. School nurses took their places as permanent public servants, responsible for the well-being of all of the City’s children—in the home and in the school, from infancy forward.

Within six short years, nurses had proven that they could do much more than treat sick schoolchildren. They had also assumed a prominent role as public health educators. They had proven that they could save thousands of lives. Wald’s vision, and Rogers’ implementation, had succeeded beyond their wildest expectations.

Bibliography

Baker, S. Josephine, Fighting For Life, NY: The Macmillan Company, 1939.

Bushel, Arthur, Acting Commissioner of Health, Chronology of the New York City Department of Health (and its predecessor agencies), 1655-1966, New York: New York City Department of Health, March, 1966. PDF available online at https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/history/chronology-1966centennial.pdf

“Official Reports,” The American Journal of Nursing, Vol. 9, No. 1 (Oct., 1908), pp. 56-64.

“Professional Nursing in School and Tenement,” New York Times, August 27, 1905

Schumacher, Casey, “Lina Rogers: A Pioneer in School Nursing,” The Journal of School Nursing, October 2002, vol. 18, no. 5, 247-249.

Copyright Anne M. Filiaci 2016

< Previous